Another year of stories to tell, some of which will take us back to the past

Here we go again. Another New Year – 2026. How many New Year

resolutions have you signed up for this year? Here at Alice’s Table,

we have two; to continue our stories and to keep you both informed and

entertained. And now with the festive season over it is once again

down to serious business. Yes, I realise today is a Friday, and that

is because from now on you can look forward to this weekly column (in

its eighth year) a little earlier on in the week – as we now publish

on Friday. Nothing else will change I can assure you. Now, just like

in the past few years we begin this New Year with a look back into our

past – but instead of the directories we pick up the Gibraltar Annual

Colonial Reports. These were published yearly for a very long-time

giving insight into Gibraltar as far back as 100 years ago. And this

is where we begin in 1926.

100 years ago – 1926 – Gibraltar was deep into the coaling trade at

the port – a very active part of our business community then. But as

we all know everything that happens outside our shores – life as it

happens away from the Rock, even today, as we are all made aware, also

reaches us eventually. Well, 100 years ago it was no different as the

Gibraltar Report highlighted when informing on the prolonged coal

strike in England that year which “unfortunately, caught the local

merchants with low stocks”. This meant the coal merchants could not

meet the increased demands and were “compelled to ration” their

customers.

The escalation of the coal dispute in Britain led to the General

Strike in May of 1926 and has been referred to as one of the most

dramatic confrontations between labour and government in British

history. Mine owners wanted to cut miners’ wages and extend working

hours. The Trades Union Congress (TUC) called a general strike in

solidarity with the miners when 1.7 million workers walked out.

Coupled with this was the fact that in 1926, both Oran and Algiers,

major cities in French Algeria, remained under their firm colonial

administration. Both cities were in direct competition with Gibraltar

and the total number of tons of coal taken as bunkers in 1926

continued to show a decrease when compared with the figures for the

previous year (1925).

Tourism has always been one of the pillars of the local economy – and

1926 recorded some improvements in the tourist traffic arriving at

Gibraltar. That year saw 30 more tourist liners in port compared to

the previous year.

As a result of the cheap summer fares introduced by Gibraltar and the

Oriental Steam Ship Company – “a large number of persons” disembarked

at Gibraltar en route for Morocco and the South of Spain.

Gibraltar in addition to attractions of its own, formed an ideal

centre from which to visit these districts, and a committee, on which

shipping, hotel and tourist interests were represented, and being

appointed then with a view to considering what steps could be taken to

popularise Gibraltar as a tourist destination (sounds familiar?).

GIB2

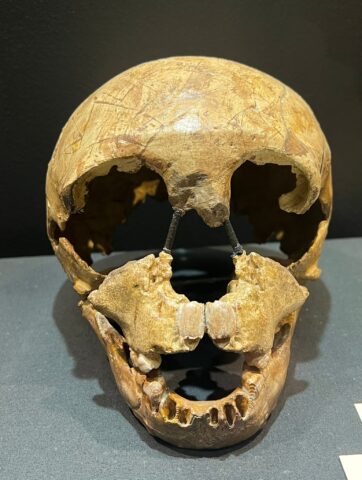

1926 saw excavations carried out at the North Front by Dorothy Garrod

working under the direction of Breuil, one of the foremost authorities

in Europe on Palaeontology – the frontal bone and other portions of a

human skull, together with implements of the Mousterian age, were

discovered on 11 June 1926 – yes, we celebrate the 100th anniversary

of that find this year by the archaeologists who uncovered the

Neanderthal child’s skull at Devil’s Tower Cave on the northern side

of the Rock of Gibraltar.

This fossil is officially known as Gibraltar 2 but today we refer to

it as the young boy Flint. Garrod was a pioneering archaeologist who

later became the first woman to hold a chair at Cambridge University.

The Mousterian is a major Middle Palaeolithic stone tool culture, best

known for its association with Neanderthals in Europe – and we

certainly know all about that with Mousterian tools having been found

in both Gorham’s Cave and Devil’s Tower. I also understand this will

be the theme of this year’s Calpe Conference in September - and

something to look forward to.

THE REPORTS

The annual colonial reports were published by H.M. Stationery Office

in all British colonies and protectorates from around 1840 to the

1970s – and were also referred to as the Blue Books. Bahamas,

Barbados, Bermuda, Ceylon, Cyprus, Gold Coast, Hong Kong, St Lucia,

Seychelles, Mauritius, Sierra Leone – these countries and many others

saw colonial reports published annually just like Gibraltar. The

colonial annual reports presented details on administration, finance

(revenue/expenditure), statistics, trade, health, education,

population, events and society.

1936

Here is an interesting note from 1936 – 90 years ago – and the start

of the Spanish Civil War when the “normal” population was very

considerably increased as a result of the military uprising in Spain

which occurred 18 July that year during the annual fair in La Linea –

“the number of refugees who poured into the colony has been variously

estimated, but it is thought probable that it was not less than nine

or ten thousand. Many of these refugees were gradually evacuated to

those parts of Spain which were held by the Government troops, while

others were induced to return to their homes in the Nationalist zone”.

It was estimated that, at the end of the year, some 4,000 of the

refugees remain on the Rock.

The value of the Spanish peseta for the first seven months of that

year was just under seven pence (7d) but on the outbreak of the

Spanish Civil War no “quotation” was available.

Prior to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, overland mail from

Gibraltar reached London and vice versa in about three days. But since

the start of the war the arrival of mail was confined to the days when

mail-carrying steamers reached Gibraltar homeward and outward bound.

Mail also arrived at irregular intervals during the war from Tangier.

Meanwhile, the total civil population at the end of the year was

19,194 – of those, 16,875 were “fixed” residents. The report points

out that these figures represented the population “between sunset and

sunrise”, or the population who resided and had a home in Gibraltar.

That year there were 175 reported cases of infectious diseases

compared to the previous year (1935) when there were 261 cases. 1936

saw a minimum number of measles cases which resulted in the low number

of cases overall. The year also saw 45 cases of diphtheria, 17 cases

of enteric fever – both with two deaths as a result. But it was

pulmonary tuberculosis which reaulted in the greatest number of deaths

with 19 deaths reported during the year.

Statistically the death rate in 1936 per 1000 of population was one in

20. Interestingly there were 365 primary, and 310 vaccinations carried

out during that year.

The medical complement saw an additional medical officer with special

experience in treatment of tuberculosis appointed to the staff at the

Colonial Hospital. It was reported that an out-patient clinic for

consultation, treatment and advice was to be opened early in the

following year.

August 1936 saw the setting up of a Commission to investigate the

housing issue in Gibraltar by the Governor. It met on 33 occasions and

“examined 31 witnesses”. The Commission members also visited “the slum

areas in the Colony and inspected various sites and premises”.

The housing problems according to the report – some of which were

dealt with -included overcrowding, slum clearance and rehousing,

finance, improvement of the housing of the working classes, rent

levels and management of Crown Properties.

According to the report the “majority of the age-earning population”

lived in tenement buildings and small flats consisting of two rooms

and a kitchen – where “overcrowding” was widespread.

1946

The year following the war in1946 - 80 years ago – continued to see

the repatriation of the civilian population which had been evacuated

during the war – 16,700 men, women and children to the UK, Madeira and

Jamaica. The year was one of steady progress in the restoration of

“normal” facilities and the expansion and development of social

services. The repatriation of evacuated Gibraltarians continued

throughout the year with some 2,000 people remaining in camps in

Northern Ireland as well as some 1,600 in different areas of the UK,

and elsewhere. But the progress of repatriation got slower as all

available accommodation had reached crisis point. The shortage of

housing was nothing new – it had always “been acute” but now the

situation was worse as many of those returning had no accommodation in

Gibraltar having lived in Spain for most of their lives following

their return to the Rock at the outbreak of war.

This would lead to serious overcrowding in the initial stages… but

there was an active policy of providing temporary housing

accommodation for the returning evacuees which would continue

throughout the whole year. 74 concrete houses were completed, newly

erected Nissen huts provided 177 dwellings, and some existing large

houses were converted into small flats. Many of the bombed properties

were also repaired and made habitable. And there was also progress

made on small permanent housing schemes.

The total number of persons accommodated in temporary houses, housing

centres and converted buildings up to the end of 1946 was about 2,500.

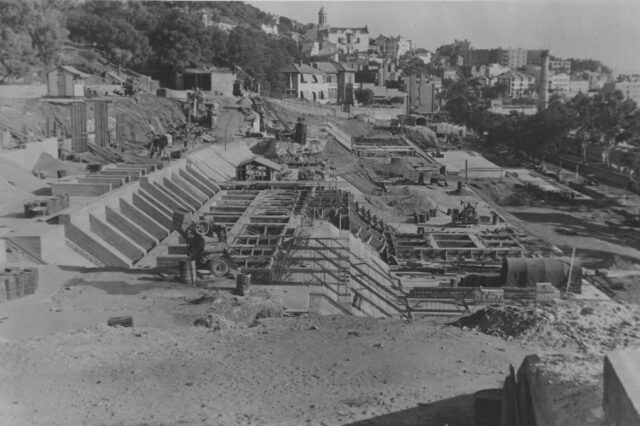

It was then that detailed plans were drawn up for a large permanent

housing scheme.

Estimates were made, tenders received and a contract entered to

building 472 flats – this would become Humphreys.

In 1946 cultural activities in Gibraltar centred around the Calpe

Institute which was directed by the British Council, and the Gibraltar

Literary Debating Society, which was an independent body managed by a

committee of which the Command Education Officer was secretary. The

British Council was especially prominent in the encouragement of

dramatic and musical talent. Three dramatic performances and two

symphony concerts were given during the year. Other activities

included talks, lectures on art and culture, and the inauguration of a

successful art group under the direction of a local artist, a

photographic group, which held an exhibition of its members. There was

also an active chess group.

1946 as well saw the reopening of the Gibraltar Museum which had been

closed since 1939 at the outbreak of war. It was re-conditioned and

reopened to the public in November 1946.

1966

1966 - 60 years ago – Spanish measures against Gibraltar continued and

intensified. The measures had begun in October 1964 when the United

Nations Committee of 24 called on Britain and Spain to hold talks

about Gibraltar. In 1966 – delays on all motor vehicles entering or

leaving Gibraltar continued throughout the year. At the peak tourist

period in July tourists travelling from Morocco were being held up for

as much as three days at the frontier. In August that year some 2,000

Spanish women who had worked in Gibraltar daily, many for a lifetime,

were prohibited from working here by the Spanish Government.

By September tourists’ excursions from Spain to Gibraltar were

unofficially discouraged by the Spanish Government. The frontier gates

were finally closed to all vehicular traffic in October.

The ban on exports from Spain to Gibraltar was then also made complete

by including fish, fruit and vegetables.

Although the measures imposed were serious and aimed at strangling

Gibraltar by the end of the year it was clear the Spanish blockade had

failed to cripple Gibraltar’s economy or to weaken the stand of its

people.

In 1966, the Report points out that there were several relatively

small industrial concerns engaged in tobacco and coffee processing and

bottling beer, mineral waters, etc. – and all mainly for local

consumption. Others at the time were also engaged in meat canning and

in the manufacture of cotton textile goods, produced mainly for

export.

There were 12 Government primary schools in Gibraltar in 1966 and

three Private schools. By the end of the year there were 2,599 pupils

enrolled in Government schools, and 618 in Private schools making a

total of 3,217. Milk was provided for all pupils in Infant Schools and

for those pupils in Junior schools for whom it was considered

necessary. School clubs and societies of many types were organised in

most schools – and there had been for many years a very active Girl

Guiding and Boy Scouts movements. There were 245 full-time teachers in

Government and private schools in 1966 – 139 had received training and

106 were untrained - 10 of them were men and 96 women. The report

points out that most of the untrained staff had received secondary

education up to the standard of five passes at GCE O’ Level, 40 were

recruited from overseas (28 of them members of a Religious Order),

three were recruited through the Ministry of Overseas Development for

service in Protestant Primary Schools, and the rest are attached to

the Gibraltar and Dockyard Technical College and Brympton Private

School.

That year 13 students, five male and eight female, went to college in

Britain in September – that made a total of 45 teachers being trained

in the UK – 24 males and 21 females.

Adult Education and Evening Classes continued to be on the increase

and remained popular – they were organised at the John Mackintosh

Hall. The subjects offered included English, Mathematics, Dressmaking,

Art, Pottery, French, Spanish, Book-Keeping, Typing, Shorthand,

Keep-Fit, Russian, Cookery and Woodwork.

And on a cultural note – let us turn to the Saturday ‘pop’ concerts,

and Sunday concerts of recorded classical music at St. Michael’s Cave

which continued to gain popularity during 1966. In October that year

there was a Non-Stop Pop Session with 1, 241 people attending. The

total number of those attending throughout the year were 7,888 for the

Pop concerts, and 4,109 for the recorded classical concerts.

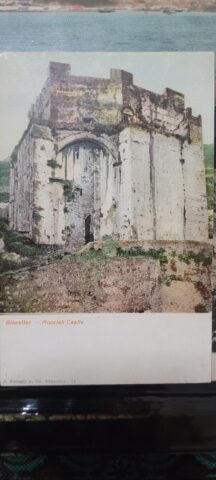

And as to how many tourists visited the Gibraltar sites by the end of

1966: St Michael’s Cave – 52,015. Upper Galleries – 17, 207, and the

Moorish Castle 5,931.