Border history continues to shape Gibraltar’s political identity, Garcia says

Deputy Chief Minister Dr Joseph Garcia [left] pictured at the exhibition with Government Archivist Gerard Wood. Photos by Johnny Bugeja

The border is a barometer of Gibraltar’s relations with Spain that for decades has “defined” this community and its modern political development, Deputy Chief Minister Dr Joseph Garcia said on Thursday.

Dr Garcia was speaking as he presented a new exhibition prepared by the team at the National Archives to mark this year’s 40th anniversary of the full border reopening on February 5, 1985.

“[The border] has scarred successive generations of Gibraltarians and it has, at different times and for different reasons, been at the centre of political controversy,” Dr Garcia said.

“First through mounting restrictions and economic sanctions, then by means of closure and then by its reopening.”

“Those crossing the frontier have often been subjected to disproportionate and politically motivated controls, deliberate and upon instructions from above.”

“Other times those crossing have been subject to the will of individual officers.”

“In short, those controls at the land border have often been used as a weapon of coercion against Gibraltar.”

“And it's very fitting that the elimination of those controls is now very much on the agenda, with a welcome exemption from the stamping requirement of the Schengen border code for many of us in the meantime.”

Dr Garcia acknowledged that the prospect of immigration controls at the border being removed under the treaty had made many people uneasy.

But he said that, with or without checks, “Spain still ends where it ends, and Gibraltar still starts where it starts.”

The exhibition narrates the “ups and downs” of land access between Gibraltar and Spain.

The border was first reopened for pedestrians in 1982 and then fully in 1985, 10 years after the Spanish dictator General Franco died, with the gates remaining shut for longer under the transitional democratic governments of Spain than under the blockade.

The border closure was the product of Franco’s obsession with Gibraltar over the welfare of his people.

For the Gibraltarians too, the closure had “profound consequences”, impacting every area of life.

Politically, the closure strengthened Gibraltarians’ determination to resist the Spanish dictator and became “a nation-building moment”, Dr Garcia said.

When the opening came, it was seen by many as “too little too late”, a decision motivated by Madrid’s desire to join the then European Economic Community.

Spain wanted something else too, and both the Lisbon Agreement of 1980 and the Brussels Agreement of 1984 were the price tag.

“That price was for the sovereignty of Gibraltar to be put on the negotiating table for the first time, implicitly under the former and explicitly four years later under the latter,” Dr Garcia said.

“This, unsurprisingly, caused outrage in many quarters.”

“So the opening of the frontier was covered in controversy. It was not seen as a democracy, writing the wrongs of a dictatorship.”

“Instead, many came to regard it with legitimate suspicion and with distrust.”“So the politics of the land frontier went on to define Gibraltar for decades after it opened, just as it had done before.”

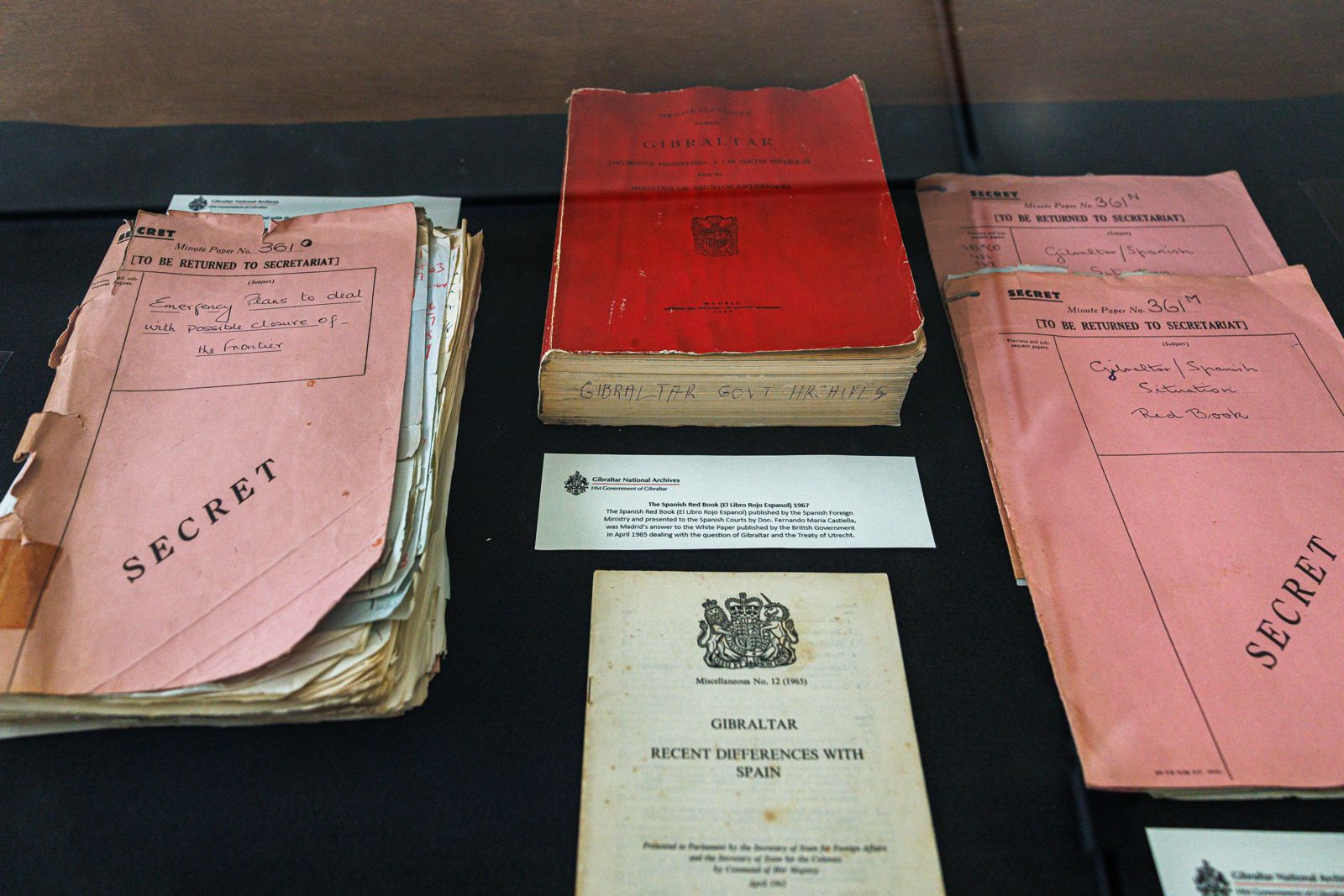

The exhibition is divided into different sections, including an analysis of UK and Spanish views on the frontier; the history of the cross-frontier workforce; the frontier closure; the reopening of the border in 1985; and the present situation with the treaty.

It includes archive material from Gibraltar and from La Linea, which allowed “exceptional” access to Gibraltarian researchers, said Gerard Wood, the Government Archivist who led the team that researched and curated the exhibition.

This first research foray into La Linea could lay the foundations for more formal collaboration in future, he added.

Mr Wood also highlighted some of the facts that had struck the researchers most as they conducted their work.

He noted, for example, that while cross-border workers accounted for some 30% of the Gibraltar workforce at the time of the border closure in 1969, that figure had risen to 50% by 2018, underscoring both the employment opportunities available in Gibraltar, and the extent to which the Rock relies on labour from the Spanish hinterland.

Even in 1969, those workers came from further afield than La Linea, including from places such as Ronda and Conil.

Mr Wood noted too that, although unions were banned in Spain under the Franco dictatorship, Spanish labourers in Gibraltar were allowed to organise themselves to put pressure on their employers in Gibraltar.

“With every exhibition, we always take away something new, and as historians that’s what we love,” Mr Wood said.

The exhibition in the John Mackintosh Hall opens to the public on Monday and runs to September 26.