Carmina Burana. Part 1

By Charles Durante

The title of this article may seem strange and enigmatic, but in fact, it just means ‘Bavarian songs or poems from Bavaria.’

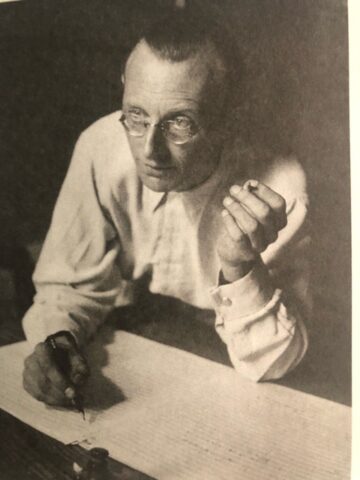

Burana is the Latin for the monastery of Benediktheuern in Upper Bavaria, founded in the eighth century, where the original thirteenth century manuscript was kept in the library. The manuscript was discovered uncatalogued there after the suppression of the monastery in 1803 during the Napoleonic reforms. It contains about 350 poems and songs, many of them unique, of which about twenty pieces, or extracts, were set to modern music by Carl Off.

Listening to the tunes and lyrics is an unforgettable experience and the songs haunt you forever. Most are in Latin, but the volume has scraps in various European languages and important pieces in Middle High German, which are among the oldest surviving vernacular songs. The manuscript of the Carmina Burana is by far the finest and most extensive surviving anthology of medieval lyrical verse, and it is one of the national treasures of Germany.

The book is now housed in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich. The library is an enormous classical building in brick and painted in yellow. It was opened in 1843 and has four sculpted giants seated on pedestals outside, Thucydides (history), Homer (literature), Aristotle (philosophy) and Hippocrates (medicine).

Because the Carmina Burana is classified as a ‘Tresorhandschrift,’ the highest grade of importance in Munich, scholars handling the book must wear gloves. The book’s binding is about 10 by 7 inches, brown and not very attractive. It has a single clasp and catch which are late medieval and they are engraved with the words in gothic script ‘ave’ and ‘maria.’ Devotional words such as ‘Ave Maria’ are quite common in medieval German book bindings; they are consistent with the text which we assume was once bound for a religious community.

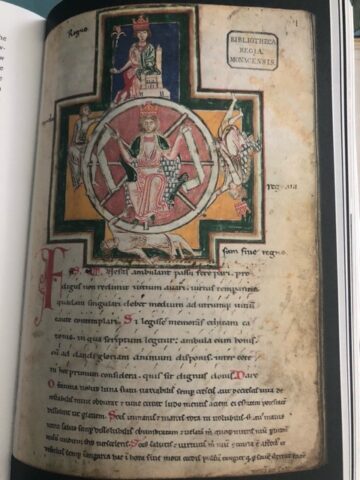

On the first page of the manuscript is the famous signature image of the Wheel of Fortune, depicting a king presiding at the top and then tumbling down as his crown falls from his head and finally lying crushed at the foot of the wheel. At the foot of the page, added in six tiny lines crammed into the lower margin, not even part of the manuscript as originally written, are the words rendered iconic by Carl Orff’s staccato drumbeats and clashes of cymbals: ‘O fortuna, velud luna, statu variabilis, semper crescis aut decrescis, vita detestabilis…….’ ‘O Fortune, like the moon, ever changing, eternally you wax and wane, dreadful life.’

A cursory glance at the manuscript would suggest that you were examining a Breviary.

A Breviary was (and for monks still is) the standard compilation of psalms and readings for the church year recited during the daily offices from Matins to Compline.

A Breviary was an easily portable book, sometimes called a ‘portiforium’ for that reason, often written in quite informal script (unlike a Missal). The earliest Breviaries in Germany date from around 1200, precisely the period of the genesis of the Carmina Burana. The resemblance is not merely in shape and size, but also in the page layout with nearly every sentence beginning with a red initial (rubric), like the verses of psalms, and the insertion here and there of specimen lines of musical notation above the script, as often in Breviaries. Some of the songs actually open with words as psalms familiar from Breviaries, such as ‘Bonum est’ and ‘Lauda’.

Scholars have detected that the love poems of the Carmina Burana follow a sequence from spring to autumn: so does the summer volume of a Breviary, from Easter to the last Sunday before Advent. The content of the manuscript can be divided into the following genres: moral and satirical poems; love songs, opening with the heading ‘Incipiunt iubili’ (songs begin); drinking and gaming songs; religious dramas. We shall try to examine at least one example from each genre.

Most of the satirical poems are on the eternal themes of the corruption of morality in modern times, such as ‘Ecce torpet probitas’ (‘See how decency is moribund’), and how the world is no longer governed by virtue but money instead. There are poems on the harshness of fortune, including ‘Fortuna plango vulnera’(‘I sing the wounds of fate’) and the famous ‘O fortuna, velud luna’ already mentioned.

The love songs form the longest and most famous section of the Carmina Burana. There are about 188 of them. They are all copied out as if they were blocks of consecutive prose and the rhyme patterns are hardly noticeable until you start to read out loud.

Some poems describe love affairs of history, such as that of Dido and Aeneas, but most pretend to recount personal experiences of romantic encounters or unrequited passion.

Many begin with descriptions of springtime when young men’s thoughts turn to love. That was a common convention in the first lines of medieval secular poetry. In the Carmina Burana there are many pastoral maidens in sunny meadows and randy lads seizing opportunities, or pining in vain. Here are the opening lines of one of the love songs:

Vere dulci mediante,

Non in maio, paulo ante,

Luce solis mediante,

Virgo vultu elegante

Fronde stabat sub vernante

Canens cum cicuta

(In the middle of sweet springtime, not in May, but a little before, as the bright sun shone, a maiden with a pretty face stood under the green foliage playing a pipe).

The poet goes on to praise the girl’s beauty, ‘nimpha non est forme tante,’ ‘no nymph has such beauty.’ She flees with her flock (evidently she is a shepherdess), but the young man catches up with her, offers her a necklace, which she scorns, but he nevertheless pins her to the ground and kisses her, or more, and afterwards her only concern is that her father and mother should ever know, and especially not her mother, who, as the girl says, is worse than a serpent. It is a fairly conventional love situation, but it is treated with a certain freshness and lightness.

We will cite one more love song, more complex and elaborate, and a much better piece of literature.

Dum Diane vitrea

Sero lampas oritur,

Et a fratris rosea

Luce dum succenditur

Dulcis aura Zephiri

Spirans omnes etheri

Nubes tollit, sic emollit

Vi chordarum pectora

Et immutat cor quod nutat

Ad amoris pignora……….

This is the moon rising at dusk, lit by the setting sun: ‘When the crystal lamp of Diana rises late and when it is ignited by the rose-coloured light of her brother, the sweet breath of the west wind carries all cloud from heaven, and so too it softens souls by the power of its musical strings, and it transforms the heart faltering from the efforts of love’.

It is a poem about drifting gently into sleep, after the exertions of love. The poet’s eyes close to the sound of nightingales and the wafting scent of rose petals under a tree. If you listen to Carl Orff’s musical rendition you realise what a beautiful love poem this is.

In a second article we shall explore examples of drinking songs and poems with an obvious religious meaning.