Languages and the EU

By Brian Porro

Over the last short while I have noticed several stabs at guessing the number of official languages for EU purposes and at least one suggestion as to the impact of translation on the timetable for the publication of EU official documents, in our case of the much-referred-to EU-UK Treaty in respect of Gibraltar.

Some might argue that, since Brexit — and even after any treaty — knowledge about the EU is somewhere between optional and academic but, as my late mum used to say, el saber no ocupa lugar.

For your readers who may be interested in the mechanics of the EU’s language policy, I will, as a former ‘mechanic of the EU’, provide a few points of interest. But for the majority of us who are more interested in picking up the main point before moving on to the obituaries columns to check our name is not listed, here are, first of all, the answers to the unasked questions. The bonus is that they can come in handy in the next pub quiz.

How many official languages does the EU have? 24

How many Member States does the EU have? 27

How come there are not 27 official languages? Some countries share the same language, such as Germany and Austria. Others don’t have their own, such as Belgium (there is no ‘Belgian’ language) or Luxembourg (Luxembourgish was not put forward by Luxembourg - it only notified its official language: French).

Below is a list of the official languages of the EU and the year they were adopted as such.

1958: Dutch, French, German, Italian.

1973: Danish, English.

1981: Greek.

1986: Portuguese, Spanish.

1995: Finnish, Swedish.

2004: Czech, Estonian, Hungarian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Maltese, Polish, Slovak, Slovenian.

2007: Bulgarian, Irish, Romanian.

2013: Croatian.

DRAFTING AND TRANSLATION

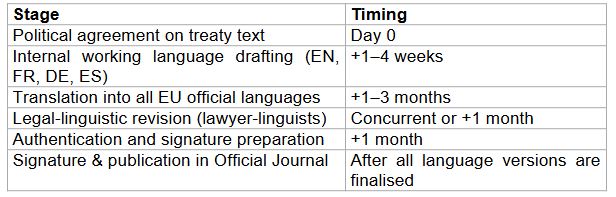

If we take ‘our’ treaty as an example, it is being negotiated and drafted in all the languages the reader can readily imagine: English, French, Spanish ...

When a draft is agreed, it will be sent to translation into all the [remaining] official languages. That will happen at the same time, so all the language departments will have the same deadline. From a translator’s point of view that is never long enough, but the typical range is from 4 to 12 weeks.

That translation will still require legal-linguistic revision by the Lawyer Linguists, dual qualified experts in the Commission, the Council and the Parliament. They check that, while each language version is accurate, it is also ‘effective’ in terms of the legal language of each Member State. Moreover, they must all exactly match each other (‘concordance’), since each language version is, itself, ‘authentic’ in the legal sense and will not be considered a translation of any ‘original’.

The good news is that the lawyer-linguist check can occur concurrently, as the text is being translated, and that foreshortens the time required and improves the chances of allowing adjustments to the translations as they are being worked done, rather than waiting to the end of that process.

SIGNATURE AND PUBLICATION

The treaty is then finalised, authenticated and published simultaneously in all the languages, with none of them having ‘primacy’ as any kind of original.

Far from being an afterthought or add-on, translation is central to the process - the aim being to maintain legal certainty and equality among all the official languages of the EU.

‘LANGUAGE REGIME’

Articles like these usually start with the legal framework setting up a procedure like the use of languages. I thought I would leave it until now for those of you who might appreciate knowing the sources.

“The language regime” is just the posh way of saying “the body of rules governing the use of languages”.

It was such an important matter for the founding Member States, such as Belgium with four languages within its borders, or Luxembourg with three, that the regulation on the use of languages and translation is one of the earliest pieces of procedural legislation: Regulation No 1 of 1958.

In the early years, with six founding Member States sharing four languages, it was easy to keep the undertaking to translate all official documents into all the official languages and to use them all as working languages. Belgium, The Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, France and Italy, shared French, German, Dutch, and Italian. However, this is such an important principle – that every citizen is entitled to have access to the law in his or her own language – that it continues to apply regardless of the number of new languages which may come into the EU Institutions. As new States join, where there is a new language, an update is made to Regulation No 1 of 1958 to reflect the new full list.

Brian J Porro is a former Senior Lawyer Linguist of the Court of Justice of the EU and a high-ranking EU Official (AD 13) in the Commission.