Remembering WWII through the eyes of Gibraltarian child

By Ronnie Barabich

Joe Gingell’s recent announcement that he is writing a new book about his Second World War experiences, which is to be entitled “When the War came to Gibraltar”, has prompted me to write about my own WWIl experiences, which will be similar, but not the same as his. In doing so I am hoping to promote his project and encourage donors to help him finance his book which he is aiming to publish in May. His book will of course be much more detailed than this, my modest contribution.

When people of my generation talk between them about “the war”, it is obvious to them that they are referring to the Second World War. This is far from obvious with respect to the young generation. Naturally the number of persons having first-hand experience of WWIl is fast disappearing. Hence the importance for such experiences to be recorded for posterity.

I am a “war baby”, having been born in April 1940 into a world in turmoil, some eight months after the outbreak of WWII on 3rd September, 1939. Although, when they got married, my parents lived at the top of Lime Kiln Steps, I was born in my mother’s sister’s house at 17 Castle Street (“La Calle Comedia”). I was brought into the world by a private midwife called Emily.

In May 1940, the Colonial Office decided that all women, children and elderly, non-able-bodied men, infamously described by the then Governor of Gibraltar in a telegram to the Colonial Office as “useless mouths”, should be removed from the Rock in order to make way, and so as not to hinder the garrison. Able-bodied men were required to remain in Gibraltar to help the “war effort”.

My father was a part-time nursing auxiliary at the Military Hospital. His friends used to tease him and say that he was only there to change linen and empty chamber pots! Poor soul.

And so, when I was not more than two weeks old, I was evacuated with my mother and all “useless mouths” to Casablanca, in what was then French Morocco. But we were not to stay there for very long. On the 22nd June 1940, following the capitulation of France to the Germans, a Franco-German Armistice was signed under which France was divided into two zones, one under German military occupation, and the so called “Vichy France” with full French sovereignty at least nominally headed by Marshall Philippe Petain, who was in effect a puppet of the Nazis.

Following the capitulation of France, important units of the rather formidable French fleet were berthed at Mers El Kebir, near Oran in French Algeria. The British could not allow these ships to fall into the hands of the Germans and be used against them. Therefore, on Churchill’s orders, the Royal Navy’s Force “H” under the command of Vice Admiral Sir James Somerville, which was based at Gibraltar, was despatched to Mers El Kebir. Once there, the French naval commander was given the options of either scuttling the ships or sailing to the West Indies. As both options were turned down by the French commander, Vice Admiral Somerville was left with no choice but to give the order for the ships to be sunk in situ, They succeeded in sinking at least three capital ships and other units. In the process, nearly 1300 French sailors were killed.

Needless to say, this angered the French immensely and left them seeking vengeance. It so happened that there were a few thousand British subjects on French soil in French Morocco, i.e. the Gibraltarian evacuees. So they discharged their vengeance on them and pushed us out of the country with hardly any notice. With aggressiveness accompanied with insults, the poor Gibraltarian evacuees were pushed to the quayside almost at bayonet point to be shipped back to Gibraltar. They were forced to board ships which had arrived there bringing French troops from the mainland.

The ships were hardly suited to transport women and children, but worse was yet to come, and, after all, the trip to Gibraltar was really a short one across the Strait.

Once in Gibraltar, the British Colonial authorities, having decided to send the evacuees to the UK, did not want them to disembark for fear that if they did, they would not want to re-embark to be taken to the UK. Whilst the ships that transported the evacuees from French Morocco could be tolerated, over a short distance, they were far from suitable to transport the evacuees on the long trip to the UK, not least because of the lack of amenities. The menfolk in Gibraltar came to the rescue. Following great pressure exerted on the Colonial authorities, including demonstrations, they convinced the Governor to allow the evacuees to disembark in order for the ships to be made more suitable to transport human beings, after being given a guarantee that the incumbents would re-embark once the ships were ready.

I was two months old by that time. In June 1940 we were embarked, destination the UK. Despite the improvements, the ships were a far cry from being suitable, particularly as the trip to the UK took 18 days. The long journey was to avoid the German U-boats as much as possible, although the risk was still there as the Battle of the Atlantic was raging, and the convoy sailed near to Canada before heading for the UK.

Once in the UK, London in fact, the Gibraltarian evacuees were accommodated at different locations. In me and my family’s case, we were accommodated at 100 Lancaster Gate, in Bayswater Road, near Marble Arch, which I believe was a recently built hotel.

The Gibraltarians soon affectionately referred to their temporary home as “El Cien”, that is, “The 100”. It should be borne in mind that the language predominantly spoken in Gibraltar at the time was Spanish, and many Gibraltarians hardly spoke English. This resulted, to some degree, in the birth of our “Llanito” or “Spanglish” dialect. Words like “sospen” (for sauce pan), “tipa”, (for “teapot) and “cuecaro” (for Quaker Oats) etc. Incidentally I remember that because of the rationing of sugar, among many other commodities, we used to sweeten Quaker Oats with jam.

The nearest tube station from “el cien” was Queensway. The building was situated opposite the Serpentine in Hyde Park. I remember playing in the pool with a toy sailing boat, looked after by my uncle Domingo Serra who was visiting the family in London. Barrage balloons were flown from Hyde Park and there were also anti-aircraft batteries.

We had not been very long in London when the capital was subjected to the Blitz. It is noteworthy that, when we arrived in London, English children were being moved to the countryside for their safety.

Our building escaped the bombing, but I remember a nearby building being hit. It was said that Londoners liked to live near where Gibraltarians were staying because we were lucky. Very few Gibraltarians were killed in London by the bombs.

I don’t remember very much about my stay in London where I lived for four years. I do remember looking up to the sky and seeing the smoke trails of the bombers and fighters involved in dog fights. I also remember going out with my cousins when the ‘all clear’ siren was sounded following an air raid, looking for shrapnel.

“El cien” had a basement which served as a bomb shelter. My mother and I went down to the basement on one occasion during an air raid, but conditions were so bad and crowded there that my mother decided that in future she would rather risk it and stay in our room.

It must have been in the first quarter of 1944, in the build-up to D-Day i.e. the 6th June, 1944, when there were many Americans in London, that one of my cousins taught me how to ask the G.I.s for chewing-gum. I was to say “Any gum, Sir?”

One personal memory of London during the war years, was that I was prescribed glasses when not quite three years old.

And so back to Gibraltar in May 1944, when the state of the war was such that it was safe to come back to our beloved Rock. In returning to Gibraltar, we were spared the horrors of the flying bombs that fell on London.

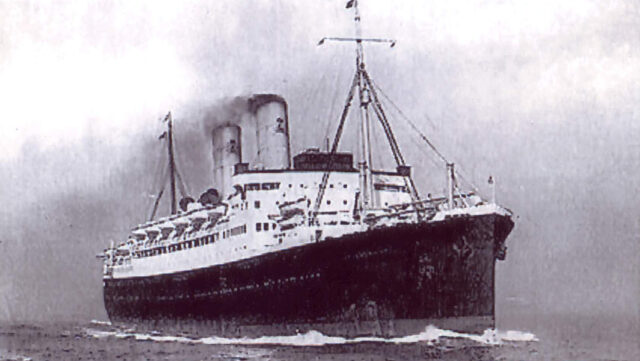

I met my father for the first time when I was four years old. Because my father, unlike other fathers, had been unable to visit us in London because he had a business to look after in Gibraltar, we were embarked on the first ship repatriating the Gibraltarians evacuees. It was called the Duchess of Richmond. I remember the emotion of the people on the deck when the Rock came into view.

My mother’s family arrived with the next lot of evacuees in the ship called Stirling Castle. There was a system by which evacuees had to be “claimed” by their menfolk in Gibraltar before being repatriated. I believe this was to ensure that those returning to Gibraltar had accommodation to go to. My father had by then rented 12/5 New Passage.

Soon after we were back in Gibraltar, there was an air raid alarm one night. We had been assigned the tunnel in Engineer’s Lane, opposite to what was at the time, or later, the Merchant Navy Club, as our shelter. In the end it was a false alarm. Remember that this was May 1944 and the war in Europe did not end until the 5th May, 1945.

It was not until 1951 that all the evacuees had been repatriated. Many spent years in Northern Ireland before being repatriated. It should be mentioned that, before deciding to start the repatriation, there had been procrastination as it is believed that the British Government were playing about with the idea of taking the opportunity of not returning the Gibraltarians to the Rock. The delay in starting the repatriation process gave rise to the formation in Gibraltar of the AACR, the Association for the Advancement of Civil Rights (of which there were very little at the time).

One consequence of couples being separated for years was that there was a certain amount of infidelity both on the part of wives evacuated to London and, more so, of the men staying behind in Gibraltar. But this must be seen in the right context. It must be remembered that when the evacuation took place and couples were separated, because of the way the war was going for Britain at the time, they did not know whether they would see each other again.

In addition, as far as the men staying in Gibraltar were concerned, they often tended to share flats. For instance, my father, his two brothers and cousins lived together in the same house. What invariably happened was they had a Spanish maid who would prepare their meals and do the household chores. This sometimes, inevitably resulted in relationships being established.

It must be remembered that Spain was just emerging from a civil war and poverty and need thrived. For a Spanish woman of the social standing that came to Gibraltar to work as a maid, to “hook” a “Llanito” was like winning the lottery. It is not surprising therefore, that married local men who had taken on a Spanish girlfriend, were in no hurry to claim their wife.

Returning to the evacuation, although the majority were evacuated to London, some went to Jamaica and Madeira. A few husbands who could afford it sent their family to Tangiers for the duration of the war. Before I refer briefly to some of the things that happened in Gibraltar during the war, I would like to mention that 1945 was a boom year for babies born in Gibraltar. Not surprising. This was later to be reflected in the demand for schools and housing.

Briefly. Following the sinking of the French warships at Mers el Kebir, Vichy French aircraft bombed Gibraltar. Incidentally, the story goes that the three 9.2” coastal guns in Gibraltar, were trained on the French fleet as it passed through the Strait on the way to Oran, but the order to fire was never given. My father told me that it seems that some French pilots were not happy about bombing Gibraltar and dropped their bombs in the sea.

There was also the case of a French pilot who, whilst attempting to come in to land in Gibraltar to join the fight against Germany, was shot down by Spanish anti-aircraft fire from army barracks in La Linea. No doubt the pilot thought that La Linea was, in fact, part of Gibraltar. My father also told me about an Italian spy plane which flew over Gibraltar at almost roof level, no doubt also thinking that it was overflying Spanish airspace, and was shot down.

Contrary to what is sometimes said, Spain during WWII was not neutral, but non –belligerent. The country was, in fact, pro-Nazi hence “Operation Felix”, a plan for the German invasion of Gibraltar from Spain by land which was never executed. Up to 1943, a total of 43 sabotage attacks on the naval base were forestalled through the use of double-agents. Two Spanish saboteurs were in fact executed in Gibraltar.

There were German spies all along the coast from Gibraltar to Algeciras, monitoring the movement of British shipping in the Bay. Their headquarters was in Algeciras. It is noteworthy that the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal was sunk by a German submarine near Gibraltar.

Most active were units of the Italian Decima Flottiglia MAS. The units consisted of human torpedoes, ridden by two frogmen. They operated from the Olterra, a 5000-ton Italian tanker scuttled in Algeciras on the 10th June, 1940, after Italy entered the war on the German side. It is inconceivable that the Spaniards did not know about it.

The modus operandi was that the front of the torpedo would be detached and attached to the hulls of ships. They were fitted with a time fuse so that the explosives would go off when the ship had left the Bay, and consequently, it would not be known whether the ship had been torpedoed or had struck a mine. Most of the Italian frogmen were either killed by depth charges or captured. They gained the respect of their enemies in Gibraltar because of their bravery.

Another important event which occurred in Gibraltar during WWII was the death of General Sikorski on the 4th July, 1943, when the plane carrying him and several Polish military leaders crashed shortly after taking off. General Sikorski was the Commander-in–Chief of the Polish army and Prime Minister of the Polish government-in–exile. The cause of the crash was never conclusively established.

It is an understatement to say that Gibraltar played an important role in WWII. Not least important is the fact that Operation Torch the invasion of North Africa by the Allies on the 8-10 November, 1942, was directed by General Eisenhower from headquarters inside the Rock. There were so many planes parked at the airport ready to take part in the invasion, that you couldn’t fit a pin.

Lastly, I will just mention one more event which happened in Gibraltar in that period. This is the way in which the Germans were deceived when an actor impersonating General Montgomery came to Gibraltar and made them think that the allies intended to launch an operation in this part of the war theatre.