From Gibraltar to the Seven Seas

The great business ventures of the Bensusan family in 19th Century Cádiz

Back in August, Brian Porro was pointed by a friend to an article spotted in the Diario de Cadiz newspaper. Written by Professor María del Carmen Cózar Navarro, an academic from the University of Cadiz, it explored the life and times of Joshua Bensusan in the early 19th Century.

This story could be seen as a companion piece to that of the Wahnon entrepreneurs, which has previously appeared in the Chronicle. In both cases, these were people with an instinct for seeking out business opportunities and for whom mere borders were just lines on a map. With that in mind, Mr Porro translated the article, with the author’s approval, and it is that text which follows below.

In the first half of the 19th Century, as Cádiz tried to regain the economic momentum it had lost after the Peninsular War and the loss of Spain’s South American possessions to independence, a young merchant from Gibraltar settled in the city. His name was Joshua Bensusan Orobida and, quietly and without drawing too much attention to himself, he would go on to become one of Cádiz’s most globally minded entrepreneurs. His story reflects a time when Cádiz looked to the sea in search of its future.

Figure 1: Josua Bensusan - Portrait held by the Family

Joshua was born in 1800 in Gibraltar into a Jewish family that was part of the Rock’s Sephardic community. Little is known about his childhood, but it is certain that he arrived in Cádiz towards the end of the 1820s, just as the port was entering a period of revival thanks to the free-port status granted to it by the Government in 1829. This measure, together with the economic liberalisation promoted under the regency of María Cristina and the reign of Isabel II, provided fertile ground for entrepreneurial initiative.

He quickly became part of the life of the city: in 1826 he converted to Catholicism [a necessary step not only to be able to hold property or public office but also to contract legally recognised marriage] and the following year married María Blanca Bergallo, the daughter of a Genoese merchant, in Cádiz Cathedral. They established their home in Calle Nueva and went on to raise a large family of seven children.

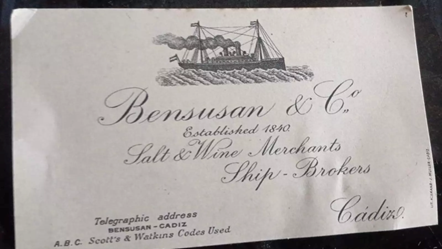

From the beginning, Joshua Bensusan dedicated himself to one of the key sectors of Cádiz’s economy at the time: acting as a ship brokers for foreign vessels. He supplied and looked after British, American, and French ships anchoring in the Bay of Cadiz. His command of English and French (together with Spanish), along with his easy-going manner, earned him the trust of many captains, as reflected in the abundant commercial correspondence that survives.

WINE, SALT AND A FOLLOWING WIND

Among the products most in demand by ships passing through Cádiz were wine and salt. Salt was not only used as a seasoning but was mostly used as a preservative in an age before refrigeration. It was highly sought after by curing industries across Europe and America, and sometimes even used as ballast when no other cargo was available. Wine, for its part, enjoyed an export boom thanks to growing European demand and the expansion of Andalusian vineyards.

Bensusan quickly got on the front foot: he acquired two saltworks in San Fernando … a winery in El Puerto de Santa María. In this way he vertically integrated his businesses, not only as a ship broker but also a producer of what he sold. This strategy allowed him to grow rapidly and begin exporting at scale — salt to South America, Newfoundland, and Canada, and wine to Europe, the Americas, and even Asia.

To achieve this, the company maintained its own fleet. The best-known vessel was the General Churruca, which made the Cádiz–Manila voyage via the Cape of Good Hope – a symbol of the global reach of this adopted gaditano entrepreneur.

ADAPT OR DIE: THE ARRIVAL OF ICE

By the end of the 19th Century, the appearance of industrial ice and the first refrigeration techniques dealt a heavy blow to the salt industry. Many entrepreneurs failed to adapt, but not the Bensusans. They diversified: in addition to manufacturing bottles, they imported barrel staves and produced wine. They also became involved in the construction of the railway in Cádiz and had shares in mining and banking ventures.

By 1865, José Bensusan (by now naturalised as a Spanish subject) was a representative of Lloyd Europeo and held 2% of the capital of Lloyd Andaluz. After his death in 1871, the company — now Bensusan y Compañía — continued to grow under his sons. The eldest, Antonio José, became Consul of Honduras, manager of the Bank of Spain in Cádiz, and a partner in major companies.

In 1910, the Financial, Industrial and Commercial Yearbook of Spain described the Bensusan firm as ‘a prestigious shipping company, exporting salt across the American continent and acting as agent for important foreign firms such as Baring Brothers of London, Bergen Kreditbank of Norway, and the Italian Register’.

A FORGOTTEN LEGACY BROUGHT BACK TO LIGHT

Now, over a century later, the name ‘Bensusan’ is absent in Cádiz street signs and schoolbooks. But the story of the family deserves to be remembered. It is the story of a family that knew how to make the most of Cádiz’s strategic location, understand the changes in international trade, and adapt to technological change. It is also the story of a Cádiz that was open to the world and which was innovative, cosmopolitan and unafraid to look beyond the horizon.

Remembering Joshua Bensusan Orobida is not just a matter of recalling his story but also a way to pay tribute to those who made Cádiz a port of the future. Because, as he proved, sometimes the greatest business adventures do not begin with a fortune, but with a clear vision, a lightly packed suitcase ... and the open sea.