Childhood memories in an area of town which once was a trendy hive of activity

Turnbull’s Lane – an area of great activity not that very long ago – where many families lived in a patio environment and which today we find rundown, derelict, and dormant. A walk in the area makes it hard to imagine that this was once a busy hive and thriving part of town with a cinema – The Rialto - which played to packed houses every night. It was not my intention to start Alice’s Table this week by writing about Turnbull’s Lane but sometimes conversations at our table take a roundabout turn revealing another episode in our past which I can never ignore. For months I had been asking Albert Danino – former headmaster at the old Bayside Comprehensive, former member of the European Movement, and artist, to join us at Alice’s Table to talk about his brother the architect and musician, the late Lelo (Aurelio) Danino of Lelo and the Levants fame, whose music was such a big part of the local sound in the 1980s. Who does not remember ‘In China’ or ‘All I want’? Knowing it was the 30th anniversary of his death this month - this coming week - I was keen to pay tribute to him with Albert’s help. Already, Alice’s Table, has featured the other members of this studio-based band (Lelo and the Levants) Oswin Falquero and Charlie Chiappe. But Lelo as we will learn next week was a well-rounded artist and a man of many talents. He was an architect by profession.

As I got chatting to Albert it soon became clear I needed to feature the brothers’ early years on Turnbull’s Lane because this is where their story begins – Lelo born in 1952 and Albert in 1954.

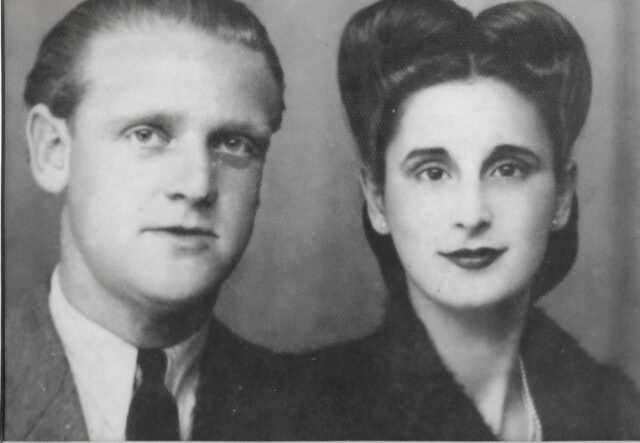

And yet, the actual story of the Danino brothers – Lelo and Albert, begins in London 10 years earlier when their parents first met. Their mother Ana (Pastoriza) at the time had moved out of the evacuation accommodation provided for the Gibraltarian evacuees in World War II.

Ana was living with her mother and cousins, the Macedos, in a house in Putney.

Their father Alberto, had been in the Merchant Navy and made his way to London to look for his mother and brother on arriving in Liverpool.

In London he also found his extended family including his aunt Victoria ‘Toti’ Chipolina who was a pianist and played the piano in concerts in Highland Heath in Kensington. Unable to house him because there were far too many of them under one roof, he was told of an attic for rent in Putney… where he would meet his future wife. The couple would get engaged in 1942. Albert returned to Gibraltar, and Ana went on to Ballymena in Northern Ireland like so many other evacuees. On her return after the war in the repatriation in 1947, – Ana and Alberto, got married and settled in with her mother in Turnbull’s Lane taking over one of the rooms in the flat. The boys came along a few years later. Alberto worked as a PWD driver after the war in a garage close to the market.

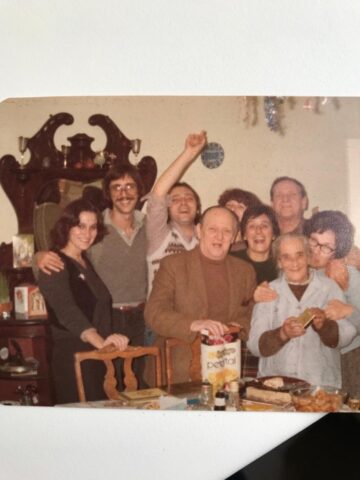

In those early days, the boys grew up in and around Turnbull’s Lane – in what Albert describes as a microcosm of a greater Gibraltar. As he picks up the story, I can tell there is great excitement in his voice as he takes me back to his early childhood - “it was fantastic growing up there”.

“We had everything – The Rialto Cinema was underneath our balcony.

There were four balconies on that building. There was Maggie’s Sweet Shop. The Barbershop with the barbers Aurelio and Diego – they would cut our hair. Short, back and sides.

“There was a restaurant called the Three Bs (Las Tres Bs) – where all the Spanish workers went (and many locals) and which belonged to Mr Perez who sold ‘comidas buena, bonita y barata’ for a few pennies. The Spanish workers would eat at the restaurant daily. I still remember what was on the menu – potajes de lenteja, de habichuelas, biftec a caballo – which was a selection of fried chips, two eggs and steak.”

Albert sometimes helped to serve the clientele at lunchtime and would earn 10 shillings at the end of the week. The place was so popular that the Spanish workers often had to queue to be served.

“These were long queues which went all the way round the lane to the front door of the restaurant,” he adds. As he continues to paint the picture of Turnbull’s Lane in the 1960s before the closure of the frontier, it seems to me, Albert retains this wonderful photographic memory of the area and his happy childhood. I found myself wondering – how could I not let him tell this story? This is a part of our past which is now gone and which if not told will be gone forever – and this is why it is so important these stories are brought to life and not forgotten. This is still my number one reason for bringing Alice’s Table to these pages – and our Gibraltar story to these pages every week.

On the other side of Turnbull’s Lane was the Smokey Joe restaurant which was run by Mr Martinez. This was where many hitchhikers, at the time, would find their way to for meals. The area also had the well-known La Bayuca restaurant which was very popular with the locals, and which was run by John and Tita Stagnetto – a restaurant which several times also served royalty, including King Charles as Prince of Wales. When the Barnacle closed its doors (just on the corner as you enter Turnbull’s Lane from the bottom of Engineer Lane) Lotties Beer Keller opened. But let us pause for a minute at the Barnacle which was one of the most popular entertainment spots of the late 1950s and 1960s in Gibraltar and where many of our well-known musicians like The Terriers cut their teeth, mainly playing for the military and navy – the troops and sailors - on the Rock. It was one of Gibraltar’s original night clubs which often stayed open until the early hours of the morning much to the chagrin of the neighbourhood.

“We lived just opposite,” Albert recalls.

“They had a licence to play music, and often late into the night everyone was wide awake – and I remember my father complaining about the noise sometimes at two o’clock in the morning. One of our neighbours decided to counterattack and played out ‘blaring’ opera from his balcony to send them a message.”

Now, between the Barnacle and the ‘Tres Bs’ there was Massetti’s ‘churreria’. As we continued down the lane was La Bayuca restaurant, then the general store ‘Almacenes Claudio’ which also sold bric-a-brac, and the Belotti Store at the other end. There was the storeroom of Elio Apap which was also well-known. It sold the popular ‘picadura’ cigarettes. Some of the Spanish ladies (matuteras) made their living by hiding the ‘picaduras’ as they crossed the frontier into Spain. But they also took sugar and saccharine, and other items which were then not available in Spain. There was one more important institution in the area – the premises of the Gibraltar United Football Club. This club was founded by Albert’s uncle, the late Aurelio Danino, a contemporary of my father, Manolo Mascarenhas, they were good friends and not only shared a passion for football and bullfighting but the world of journalism. Danino signed himself Lubinox in the El Calpense newspaper where he was the Editor for a time. Meanwhile next to the patio ‘Posso’ lived the family of the man who created ‘La Tuna Calpe’ Juan Ochello. They held their rehearsals in a room in the area close to the premises of the Gibraltar United Club.

Albert refers to the ‘lane’ as having a very ‘cosmopolitan atmosphere’

which was a hive of activity – running parallel to the Main Street. It also brought to play the many diverse characters from all walks of life who became part of the life of Turnbull’s Lane – for a young boy growing up in this area, this was totally fascinating – and in more ways than one – an education.

His brother Aurelio, he says, was more of a house boy and enjoyed reading books and model making. But Albert, a somewhat adventurous child, so he tells me, enjoyed visiting the Rialto – it was extremely popular and showed a great variety of films including Spanish, English and American movies. The Rialto Cinema was one of several cinemas in Gibraltar in the 1950s and 1960s. The family also frequented the Theatre Royal which in those days mostly showed films. In the Rialto, Albert and his friends (around the age of 10 by then), would watch whatever was showing almost every night – and his family sometimes even got in free because of a family connection as his grandmother’s cousin Jose Colombo had shares in the Theatre Royal and the Rialto Cinema.

“I remember seeing, with my brother and grandmother, some of the films by Joselito and Marisol at the Rialto. There were other films which we were not allowed to watch because we were too young but somehow, we almost managed to see them as well. The Rialto had both Spanish and English films but the Theatre Royal only had films in Spanish.”

Curious, as to how he and his friends achieved getting into the Rialto Cinema without being seen – I asked. So, how did you get to see the films? How did you get past the ticket man? With a big grin on his face, he reveals that with his friends they had discovered a gap by which they could enter the cinema via the air-conditioning area and find a spot to watch the film. The boys would work their way down to the Rialto and no one ever found out. The building in which he lived had four good sized flats at the time divided by a patio from where the family would collect their water from the pump – and fill up the ‘tinaja’. There was no running water in the house, only in the kitchen – and full body bath time was only once a week when the zinc bath was filled with hot water.

When the Cavalcade first started in 1959, Albert remembers the lorries filled with presents lined up on Turnbull’s Lane. By then his uncle Aurelio was helping and formed part of the organising committee – and he and other children dressed up as shepherds for the event to help deliver the presents. Once the frontier closed in 1969, he says, everything began to change – And The Rialto closed. The area today is almost unrecognisable – most of it has fallen into disrepair – and he tells me – “it is sad to walk in the area remembering the activity and the lively atmosphere of my childhood.”

By 1970 his brother Aurelio – Lelo, had left for the UK but not before forming his first band ‘Blossom Affair’. Aurelio enjoyed writing lyrics and his first songs. Music had a strong pull but he left for the UK to study Civil Engineering.

Albert, a few years younger, now in his mid-teens, got to know his uncle Aurelio Danino better. He had been in journalism since the war years. The young teenager was present at the many ‘tertulias’ on Sundays in his house with his father, where politics, and the issue of Spain, was always on the agenda.

“They discussed everything – the 1966 ‘Red Book’ written by Castiella and published by the Spanish Government, and your father’s ‘Palabras al Viento’ which we listened to every Sunday, the 1967 Referendum, and generally anything to do with the politics of the day. I guess that greatly influenced my thinking before I left to study in the UK.”

Albert was an outdoor person. Growing up he spent his summers at the Montagu Sea Bathing Pavilion.

“I loved it there, and I also enjoyed underwater fishing. We would also go to the jungle looking for dart bullets and old war items – always on the move, I was an explorer always enjoying the outdoors. I even remember we held races and made silver cups from the silver paper which came inside the Du Maurier cigarettes.”

As children the brothers had both been pupils at St Mary’s Infant, then Bishop Fitzgerald and finally the Grammar School. When the frontier closed in 1969, these young men and women with their future in front of them, found themselves confined to Gibraltar. For many, university became the means of escapism but it was not easy getting a scholarship.

“If you wanted to spread your wings you had to leave Gibraltar – but there is no doubt in my mind that although in those closed frontier years we may have felt confined, they were also extremely happy years because we had to make our own entertainment and be resourceful.

“We organised parties, excursions up the rock – had parties on the beach – there was always something to do. Basically, in that time of closure we found something that was meaningful, and a very exciting time. By the time I was in Lower 6th, I was organising monthly trips to Morocco on the Mons Calpe with the girls from Loreto – we would leave early in the morning – visit the market to buy vegetables, and of course make the traditional stop at Madame Porte for the cakes. We always had a great time and would sing all the way.”

Aurelio left for the UK in 1970, and Albert would follow three years later. But surprisingly Albert interrupted his studies for a year after his O Levels to work at Blands as a counter-clerk in the Aviation Department. A year later he was back in school taking his A Levels at the Grammar school. The man who would one day be the headmaster at Bayside Comprehensive (2005) was disheartened with the school system but a year later persevered and obtained his scholarship for further education in the UK.

“I always wanted to be a teacher because I liked being with young people and enjoyed the school atmosphere and the idea of teaching. I did a Degree in Languages – Hispanic Studies and French, and also spent a year in Portugal to learn the language.”

An artist himself – he had wanted to do Art but it was not possible at the time. Only 12 students achieved scholarships that year.

On his return in 1978 he first worked at the Hebrew school making deputy head and then transferring to Bayside to fill a post in languages. This is where he spent the rest of his teaching days spending five years as its head. He married his wife Angela in 1980, and they had two girls – Eva and Natalia. I notice a certain pride when he tells me they are both in the teaching profession as well. It was on moving to Bayside that he became interested in the European Movement – possibly, he tells me, influenced by Ivan Navas. They both joined as members of the movement. Years later, he formed part of the team which eventually took the fight to Strasburg so Gibraltarians could have the right to vote in European Elections.

It was during this time that European Studies were offered at Bayside Comprehensive as an alternative to a foreign language. Again, he acknowledges with pride that the subject, when introduced in the UK as a fully-fledged GCSE, Gibraltar became the biggest centre of entries for the subject in the UK at national level – “it simply proved it was not popular in the UK but in Gibraltar we felt it was very important to teach it - and in the last year we had 120 entries. But then it was scrapped by the UK boards.”

Now in retirement Albert is again dabbling in painting and recently formed part of a group of artists – his contemporaries – who staged an exhibition at the Fine Art Gallery.

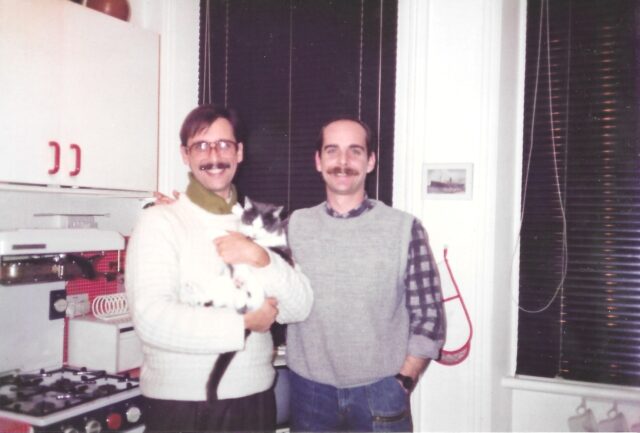

As we turned back to his brother Lelo – he reminds me this coming week will be 30 years since he passed away – one of the early victims of Aids, when still very little was known about it. Today, his aim is to keep his brother’s memory and music alive and believes that much of what he wrote is still relevant. Next week we follow the footsteps of Lelo Danino and his move to the UK and the influence of music in his life.