Christmas: a meditation

Christmas is probably the most popular religious festival which has survived into a post-Christian, secular age. Though exploited by businesses and tarnished by the extravagant buying and spending we all indulge in, it still carries a significant religious charge and expresses our yearning, with a tinge of nostalgia, for our lost childhood and happier days.

This short meditation was prompted by a reading of T S Eliot’s poem, Journey of the Magi. Though explicitly a poem about the hardships encountered by the three Magi during their gruelling journey to Bethlehem, it raises important issues about Christian belief and the exact meaning of the two Nativity accounts in the gospels of Matthew and Luke.

Eliot starts his meditation with five striking lines lifted from a Christmas sermon by bishop Lancelot Andrewes (1555-1626):

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.

Eliot was converted to Anglo-Catholicism in 1927, the year his poem appeared. You would think the poem would unequivocally celebrate his new-found faith, and the choice of Christmas and the visit by the three wise men would elicit a joyful response. But Eliot emphasises the ambiguity of the occasion and the Magi’s ambivalent interpretation of the birth of Jesus.

After the lines quoted from Bishop Andrewes, Eliot plunges into a graphic account of the perilous and uncomfortable journey undertaken by the star-led astrologers: the recalcitrant camels were a problem, the camel drivers quarrelling and cursing, deserting and always eager for sex and alcohol, the exposure to the piercingly cold night air, the towns filthy and inn-keepers “charging high prices”, the general hostility which greeted strangers who were suspected of being shifty and disturbingly foreign. No wonder that the Magus cries out: a hard time we had of it.

The experience became so painful that the star gazers yearned for their former life: the summer palaces, the girls with their diaphanous dresses and cool sherbet - but this represented their old life, the life they had renounced when they mounted their camels and faced the challenges of a journey into “terra incognita.”

Spiritually and psychologically, the strain shows when they hear voices in their ears admonishing them “that this was folly.” There is now a poetic moment of realisation when overtly religious symbols enter the poem: the “three trees on the low sky” point to the crucifixion; “the old white horse” recalls the figure in Revelation (19:11), “then I saw heaven opened, and behold a white horse! He who sat upon it is called Faithful and True,” an obvious reference to the victorious Jesus; the “vine leaves over the lintel” combines Jewish ritual and the sacrament instituted by Jesus himself; ominously, the “six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver” are both the Roman detail playing dice for Jesus’s garment and the betrayal by Judas. The poem recreates the experience of the encounter with the baby, here alluded to as “a Birth” but the meaning escapes the speaker: was this a moment of revelation or a grim brush with death? Without a doubt, when the Magi return home, they are no longer at ease, surrounded by “people clutching their gods.” They will need time, maybe a whole lifetime to penetrate the inner meaning of their experience in faraway Judea.

We have become so accustomed to the various icons we associate with Christmas that we forget many of them have no biblical foundation, but are accretions acquired over time. Even the customary ox and donkey are absent from the biblical account!

Two charismatic individuals, Francis of Assisi and Charles Dickens, have contributed significantly to the fond picture we all now nourish about the Christmas celebrations. The famous crib was probably first elaborated by Francis; the steaming goose, tree, pudding and general jollification are mainly Dickensian.

Like most of the pivotal feasts of Christianity, Christmas also has a pagan background. There is no biblical warrant for the celebration of the birth on the 25th of December. The birth narratives, in Luke and Matthew, do not mention a particular day, and it is only in the mid-2nd century, when the flourishing of Gnostic teachings doubted Jesus’s genuine humanity, that the birth was firmly anchored in time. The traditional date first appears in an almanac of 354, which carried an entry under December 25, “natus Christus in Betlem Judaea” (Christ was born in Bethlehem of Judea).

Coincidentally, this is also the date in the Julian calendar of the winter solstice, the day when the sun is reborn, celebrated by the adherents of the oriental cult of the sun god Mithras. When Roman soldiers learned about Jesus, they were reminded of their favourite god Mithras. Other gods are present but not mentioned.

With the arrival at a “temperate valley… smelling of vegetation,” in the narrative of the poem, Eliot obliquely references the many dying and reviving gods of the fertility rites: Attis, Adonis, Osiris, Dionysus and here, Jesus.

The emperor Constantine, who declared Christianity the official religion of the empire, syncretised pagan and Christian beliefs, so that as Jesus was the ‘sol verus’, the true sun, the ‘sol invictus’, the unconquered sun, it was appropriate his birth should coincide with that of the sun. The December date had an added advantage in that it was nine months after March 25, the assumed date of the Incarnation.

In the east, according to the Alexandrian calendar, January 6 was the date of the winter solstice, and this was celebrated as the festival of the Epiphany which included the manifestation of Jesus at his birth.

Eliot’s poem does not celebrate the Christmas event in a traditional, conventional manner; instead, it poses difficult questions as to the nature of the speaker’s encounter with an anonymous (for them) baby who was, disconcertingly, the King of the Jews.

Christianity is a paradoxical religion and no more so than in the birth of the supposed Word in a remote corner of the Roman empire in the form of a vulnerable baby.

The speaker of the poem is non-plussed and struggles to make sense of the experience. The vision of the baby swaddled in the manger is climactic (the lives of the Magi are forever changed), but they saw a baby and in visual terms, one baby is much like another.

The poem endeavours to give the description a poise and depth commensurate with its meanings. The Magi know deep down that something momentous has happened, but don’t have the language to describe it adequately.

They fumble in the dark, talking about a birth and a death, but seemingly perplexed as to the true import of what they have witnessed.

Eliot seemed to lack a strong incarnational sense and so his argument is theologically sound but lacking in imaginative colour and feeling. The theology is succinctly conveyed in the following lines:

And so we continued

And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

The message hinges on the word “satisfactory”, which is a pun on Jesus’s redemptive act of dying on the cross (obliquely referred to in the poem), often seen as an act of satisfaction for the sins of mankind.

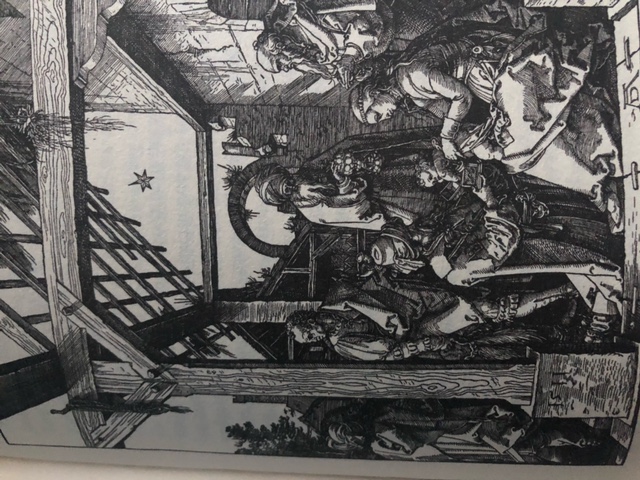

Like many a Renaissance artist, who included emblems of the Passion of Christ in paintings of the Madonna and child, Eliot has incorporated hints of the passion in what is purportedly a Christmas poem.

The Dickens Christmas, described in the Pickwickians’ celebration at Dingley Dell and in the festivities in the Carol books, is one of feasting, storytelling and merrymaking. It is also a time for reflection and for expressing one’s common humanity in charity.

Dickens has been variously described as Father Christmas and the inventor of Christmas; he certainly deserves some credit for helping to rescue the holiday from dour Calvinists, many of whom condemned traditional Christmas celebrations as pagan rites.

Were they aware of the pagan background to the Christmas story? Probably not, but they disapproved of conviviality and indulgence in innocent pastimes.

We can but hope that figures like Francis and Dickens will inspire our Christmas and extend their influence to lands ravaged by genocidal war and internecine conflict.