La Tablita – An Epiphany

By Brian Porro

Gibraltarian émigrés probably fall into several categories. There are those who leave without so much as a backward glance, possibly rarely if ever returning, who may or may not use or keep up their Spanish or Yanito skills; those who frequently return, but are otherwise well integrated abroad; and the expatriate Yani who returns regularly, maintains a level of Yanitude while still taking a full part in the foreign setting, and who is in close touch with the day-to-day of what is happening ‘back home’.

Reader, I belong to the latter category.

And it is a style of being which often results in thinking about life in Gib, in the old days and in the present, which is what led to a conversation with another Gibraltarian abroad, while driving around the British countryside in early December about ‘La Tablita’.

We were sure about certain aspects, but uncertain about others.

There had always been one in the family, and it seemed that every sombrilla or barraca had one or sometimes, if the tribe foregathered was big enough, more than one, with several games going at the same time. Of that we were certain. As certain as we were about the general nature and origin of the boards that gave the name to the game in Gibraltar. We struggled to recall which uncle or other relative or friend of the family had made the one we used in days of yore in Hood House or on Eastern Beach, but there was much humour extracted from recalling, possibly falsely, that HM QEII had a big investment in most of the tablitas circulating in town – where did the materials come from, we wondered winkingly?

The paint probably came from leftover Airfix® kits or from unused stock from painting lo muñequito (the plastic model players for Subbuteo®, which were sent out as blank figures in plain white and painted as a cottage industry occupation by very many families in Gibraltar).

Did anyone sell them, back then? If they were made at home, how difficult could it be?

Never one to ignore a challenge, particularly a challenge with the added frisson of ‘Gibraltariana’, I thought I would make one myself. Surely it cannot be that hard, suggested my companion. B&Q, the well-known chain of DIY stores in the UK, he suggested, offer a cutting service, so just getting some wood and a bit of paint cannot be that difficult.

Artista

Noninà.

Not difficult. Pero how big were these things? How much wood would I need? As a small child, they seemed to be coffee table-sized but, on reflection, and in some dim black-and-white photos, they seemed small scaled against our various aunties’ generously-filled bathing costumes de la época. But who could tell?

We parted company and I was then free to indulge my new-found interest that would see me into the Christmas season with something around which to gather the family – or bore them.

Dear Reader, have you ever tried to find an image of one of our sacred tablitas? I did not even begin to search on paper, because we are culturally modest and are unlikely to have made it into any publication on board games, of which there are one or two out there. But search as I might on the internet, there were intriguingly small results.

Searching for images of the board, I tried the words ‘ludo’ as well as ‘tablita’, since we often imagine that they are pretty much interchangeable names, as search strings.

Plenty of Ludo boards, with which I was already familiar and knew not to be like our traditional layout, popped up. However, searching for ‘tablita’ images did bring up what I was looking for – a whole series of photos of boards produced by one particular person during lockdown in Gibraltar. That was all the prompt my memory needed to start work on my own.

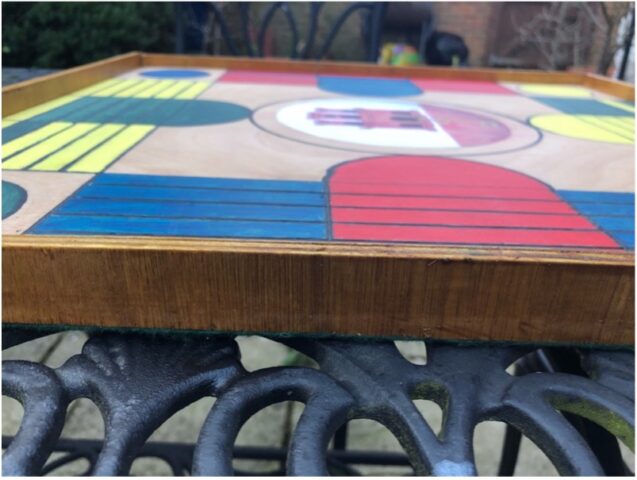

A photo is worth a thousand words, so you’ll be glad I have included one or two in this essay.

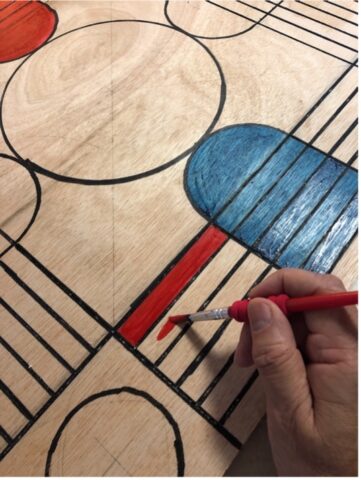

After a desk-based career, the opportunity to work with wood using a ruler, a compass, a jigsaw, glue, paint and brushes was one I welcomed each evening from December 9 to nigh on Christmas Eve, when I managed to get the last coat of varnish dried before the kids turned up.

It was precisely with the next generation in mind that I designed the board to look as if I had salvaged it from un baúl wardao de casa. Of course, that was not true, but by using antique pine varnish finish, giving the Gibraltar crest in the centre a ‘washed out’ look and making the paint look like it had been applied with a balding brush all went to give la tablita an age-distressed look.

However, that is not the end of it. In my research, trying to recall or establish what the rules of the game are, I realised something which I think could elevate the standing of the humble game of tablita in Gibraltar. It could even find a niche in our museum of Gibraltarian life and be reported in future editions of serious works on games around the world.

I discovered something quite intriguing, if not astonishing.

A voyage of discovery

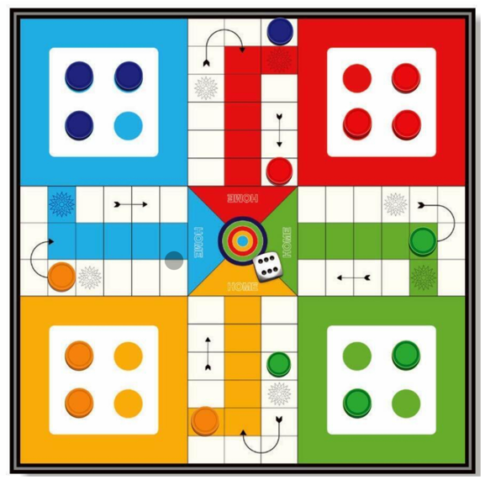

When I looked into Ludo initially for the board design, I could see that the layout is altogether different, as may be seen from the images accompanying this piece. The track or path which the players follow round the board is thinner and more stylised than ours. The colour scheme is similar and the rules are close to ours although very much simplified but, more importantly, the counters in Ludo move clockwise around the course.

More research into the story of Ludo taught me that this was a children’s version of an adult game whose roots were to be found in the India of the Moguls or earlier. The original Indian game, Pachisi (also Parcheesi, Parchisi, or Parchesi), found its way probably via two routes into Europe: with the Portuguese and Spanish into Southern Europe and via the British and Dutch into Northern Europe. In Britain, it became ‘Parkase’ and was reportedly popular with Queen Victoria. The game was an adult affair and vied with card games for betting and entertainment. It was not deemed suitable for children, which is why Ludo was developed and marketed in 1896.

Additionally, there is a ‘grown up’ reverse development of Ludo, known as Uckers, which the British Royal Navy devised, with more rules and more forfeits. For example, under certain circumstances, if a player disputes a rule or a move, that may lead to an invitation to check the rules. In Uckers, the rules are traditionally stuck on the underside of the board, so it is tantamount to tipping up the board. What follows is anybody’s guess.

However, the board is very much the same design as for Ludo.

Parchís and Parcheesi

Turning to the other descendant of the Indian Pachisi, the Spanish Parchís, was a voyage of discovery. I had often heard it mentioned on Spanish television programmes but I had no idea how close or distant from Ludo it is.

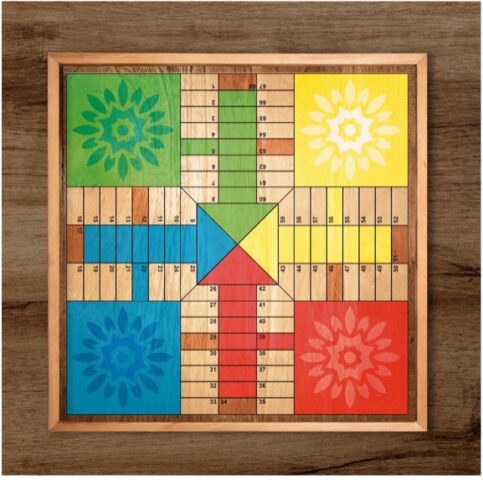

The rules are more complex than for Ludo and are largely shared by Tablita, but the board is quite different.

As can be seen from the picture, the colours and general layout, cross-and-circle, are recognisably similar to Ludo and somewhat similar to la Tablita, but Parchís is less colourful and has more spaces (numbered from 1 to 68, plus the ‘home runs’) and has three ‘safe spaces’.

In the United States of America, the game was marketed as ‘Parcheesi’. Selchow and Righter trademarked the game in 1874 and it became their best-selling game for many years. The rules are very similar to those for Spanish Parchís.

Parqués

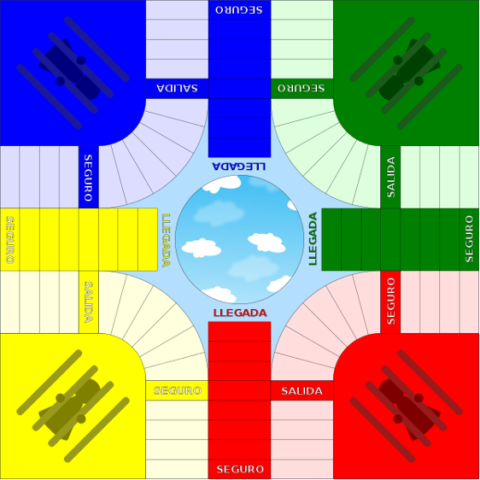

A further ‘variant’ of Pachisi is Colombian Parqués.

The claim in Colombia is that this game arrived direct and separately there via the ‘coolies’ – Asian indentured workers from the Indian subcontinent – brought by the British empire. Although the rules and the layout are very similar to Parchís and Parcheesi, Colombians strongly claim that the game is purely Colombian and that it is not played in any other Latin American country.

According to the Colombians, their game is ‘completely’ different from Parchís (or indeed from Parcheesi), except for the rules and the layout of the board. Admittedly they have slightly different names for ‘la casa’, referring to it as ‘la carcel’ or ‘gaol’, and having their own names for certain of the rules. The game is generally played with two dice.

And yet it is claimed as a uniquely separate national game by Colombia.

A Game with Pedigree

So where does that leave our Tablita?

I say it leaves it in a unique position. The board shares certain characteristics with Ludo: the spaces are, as in Ludo, fewer than Parchís at 6 steps on each side, as can be seen from the accompanying pictures, and there are no numbers.

However, unlike Ludo, the game moves around the board counter-clockwise and the rules provide more of a challenge.

But the most outstanding difference between Gibraltar’s national board game of Tablita and all the others is the pattern of the playing area. As can be seen from the images, the three tracks on the four sides are coloured and are of equal width, covering the full area between the two starting areas (‘casas’) on the same side.

That combination of rules and layout, which I think may be altogether unique to Gibraltar, makes la Tablita a cross-and-circle game worthy of being listed alongside Ludo, Parchís and Parqués as a self-standing variant descendant of the ancient Indian game. It would be additionally wonderful if it were to be found that our game had come here also direct from India independently via our own links with the subcontinent.

For all those reasons, I think that, while la Tablita could be recognised by being accepted onto the UNESCO list of ‘intangible cultural heritage’, this may not be an entirely serious proposal. But what I hope this exploration does is lead all of us to an epiphany, a realisation that quite a few things that we do in Gibraltar, from the way we speak and cook to the games we play, are quite special and worth valuing.

The Name of the Game

Finally, oh Reader, you may scoff at the very idea, not least because of the low-brow name the game appears to bear, that ‘la Tablita’ is in any way special as a name, if not as a game.

It is true that, in typical fashion, we call the game ‘el juego de la Tablita’ as if we were saying ‘that game we play on some kind of a board’, and that it doesn’t have its own name, like Parchís or Uckers. It’s what we also do for ‘removable’ – ‘de kitipòn’ – and ‘folding’ as in ‘folding chairs/tables/legs’ – ‘de avrìyserrà’, instead of ‘amovible’ or ‘desmontable’ for the one or ‘plegable’ for the other.

Nevertheless, I would argue that the name ‘Tablita’ does have a noble precursor. In ancient times, ‘Tabula’ was a game played by the Romans and the Greeks and is an ancestor of Backgammon, and the ‘name’ means no more than little board. If such a name was good enough for the ancient Romans …

1) Yani/Llani/Gianni: our demonym appears in several forms. In order to avoid oblique strokes (/), the form suggested by Manolo Cavilla in his Diccionario Yanito has been used throughout.