The Dream of the Rood. Part 1

The main topic of this first essay is an Anglo-Saxon religious poem, composed around 800 CE, and now found in the Vercelli manuscript in northern Italy.

We must bear in mind Anglo-Saxon was the language of the tribes which migrated from the continent to Britain a couple of centuries after the Romans left. Originally pagan, they were converted to Christianity by Augustine who was sent by Pope Gregory with that specific purpose. Our poem is very much a Christian poem.

The first record of the Dream of the Rood (incidentally, rood is the Anglo-Saxon word for cross) are lines carved in runic characters on a large stone cross which stands in the chancel of the kirk at Ruthwell, Dumfrieshire. The rood, which is eighteen feet high, is perhaps the most famous single Anglo-Saxon monument, and is covered with scenes in relief and runic inscriptions in the Northumbrian dialect.

The cross is connected to the return from Rome of Coelfrith, abbot of Wearmouth and Jarrow. During the abbot’s stay in Rome, Pope Sergius I supposedly discovered a fragment of the True Cross. Then, in 884CE, Pope Marius sent King Alfred another piece of the True Cross and an expanded version of the Dream of the Rood was written.

This is now found in the Codice Vercellese. This manuscript, from around the 10th century, is now in the library of the Cathedral of St Andrew in Vercelli and contains a florilegium of religious texts.

Aethelmaer, heir of Ealdorman Bryhtnoth, leader of the East-Saxons at the battle of Maldon, had a reliquary made to hold the Alfred fragment. The reliquary has a quotation from the Dream inscribed on it. The only complete text, however, is found in the Vercelli Book.

The Dream of the Rood is the most famous Old English religious poem and is today preserved in three different forms, inscribed by hand in stone (the Ruthwell cross), on skin (the Vercelli ms) and in silver (the reliquary). The versions are written in three different dialects of Old English (there was no standard form of the language at the time). All three artefacts are found outside England.

The Dream is unique perhaps in the literature of the world, certainly in Anglo-Saxon England. The Old Testament, with its tribalism, jealous God and its vengeance ethic was more congenial to the Anglo-Saxon ‘scop’ (poet), but in the Dream the artist has chosen the most dramatic event in the Christian story: the crucifixion of Jesus.

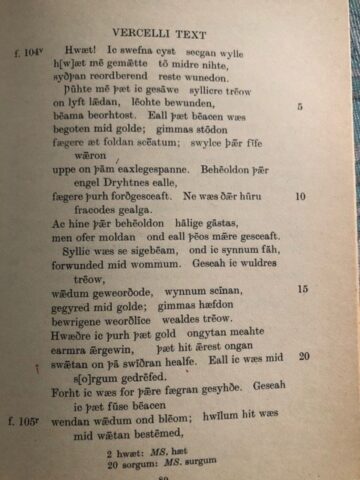

Here are the opening lines of the poem in the original:

Hwaet! Ic swefna cyst secgan wylle

Hwaet me gemaette to midre nihte,

Sythan reordberend reste wunedon

Two modern versions follow, one in verse, the other in prose:

Hwaet! A dream came to me

At deep midnight when human kind

Kept their beds

A dream of dreams!

I shall declare it. (translated by Michael Alexander)

Lo! I will relate a marvellous dream which came to me in the middle of the night when men were at rest. (version by M W Grose and D Mckenna)

The Dream of the Rood is a brief description of what could have been a mystical experience. The anonymous author is perfectly in command of his material. He tells us how the Rood appeared to him and the words it spoke. The idea of making the cross speak is not unparalleled: there is evidence the author was familiar with the Passiontide liturgy where this happens.

‘It seemed I saw the Tree itself - a beam of brightest wood, with gold, gems and five stones set in a crux and the angels of God all gazed upon it.’ The tree now speaks: ‘It was years ago. I still remember it - that I was cut down at the edge of the forest. Men set me on a hill. I saw the Lord of mankind making great haste to mount me.’ In Anglo-Saxon the last line reads like this: Geseah ic tha Frean mancynnes efstan elne mycle.’ The poet makes us trust what he saw by insistently repeating the verb ‘geseah’ (I saw). The poem then mentions the nails piercing the wood; both Jesus and the cross were reviled; the tree now is drenched in blood. This part of the poem comes to a climax with the simple but stark statement: ‘Crist waes on rode’ - Christ was on the cross. There now follow the deposition and burial. The details of Jesus’s burial are reminiscent of the burial of an Anglo-Saxon warrior. ‘Then wretchedly in the evening they began to sing a dirge when they were about to depart.’

We will now take a historical detour to examine the Latin background to the veneration of the so-called True Cross. The emperor Constantine converted to Christianity on the eve of his victory over Maxentius in 312CE. Constantine was convinced his triumph was directly related to his dream or vision of the heavenly sign of the cross. Concomitant with his adoption of Christianity as the state religion, he promoted as symbol of the new faith the ‘chi-rho’ monogram of the name of Christ and the long-abhorred cross. ‘Chi-rho’ represents the first two letters of the name of Christ in Greek, Christos. The standard of the imperial troops was remodelled, the so-called Labarum taking the form of a cross surmounted by the ‘chi-rho’ monogram. The imperial patronage seems to have resulted in the immediate popularity of the symbol.

There is a connection between our poem and the ‘Invention’ (finding) of the True Cross tradition. By the end of the fourth century an ‘Invention’ tradition, which ascribed the discovery of the True Cross to Constantine’s mother, Helena, on a visit to the Palestine in 326, was well known.

The presentation of an important cross relic by the Emperor Justinus II to Princess Radegund had been the inspiration for the two most famous cross panegyrics by Venantius Fortunatus, Bishop of Poitiers: Vexilla Regis Prodeunt and the Pange Lingua. This stimulated a long line of hymns and poems in veneration of the cross. Our poem belongs to this pedigree.

A few stanzas from the Vexilla will show the reader the similarities which bind the Anglo-Saxon poem and the Latin hymn. Even the first word ‘Vexilla’ connects the two poems as ‘vexillum’ is a standard or flag and the cross in the Rood poem is called a ‘beacen’, a symbol, sign or standard. Venantius’ second line mentions the cross shining forth: ‘Fulget crucis mysterium.’

But it is the fourth stanza which clearly shows the dynamic relationship between the two works:

Impleta sunt quae concinit

David fideli carmine

Dicendo nationibus

‘Regnavit a ligno Deus’

Thus were the prophecies fulfilled

That David sang in truthful strain,

Proclaiming to the world at large

That God did reign from on the tree.

Two more lines from the fifth stanza remove any doubt we may have about the influence of Venantius on our anonymous poet:

Arbor decora et fulgida

Ornata regis pupura

O beautiful and shining tree,

Adorned with purple of the king.

We recognise the many elements which are shared by both poems: the direct address to the cross; calling the cross a tree; the idea of Jesus as king; the purple (blood) which drenches the cross.

In a second article we shall leave Venantius’ lovely hymn behind and take a closer look at the many fascinating details of our Old English poem.