Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose Part 2

Eco’s novel has been described as a Gothic novel, medieval chronicle and detective story. But it is so much more: an ideological narrative, a puzzling ‘whodunnit’ and a theological and philosophical debate with a penchant for discussing and analysing abstruse topics like the subtleties of heretical movements which were particularly prolific at the time. It can also be interpreted as a roman à clef, so that we can spend time looking for some of the historical characters lurking behind Eco’s creation.

To appreciate the role played by different popes we need to jettison our modern idea of a saintly man, mainly concerned with spiritual matters and the running of the church.

Medieval popes were powerful figures who wielded both ecclesiastical and temporal power. Eco mentions three popes to illustrate the growing influence and hubris of the vicar of Christ.

Hildebrand of Sovana, known as Pope Gregory VII, ruled the papal states between 1073 and 1085. He emphasised the primacy of the papacy and consolidated his power in the investiture controversy (who should have the power to nominate bishops: the pope or the emperor?). He assumed one crown with the legend: ‘corona regni de manu Dei’ -the crown of the kingdom from God’s hand.

Later Boniface VIII added a second crown, announcing ‘Diadema imperii de manu Petri’- the diadem of the empire from Peter’s hand.

John XXII, who plays a prominent role in the novel, added a third crown, thereby combining the temporal, ecclesiastical and spiritual powers. This became the triple tiara which was only discarded recently by the Vatican. William is no admirer of John XXII whom he calls ‘a thieving magpie, Jewish usurer; in Avignon, there is more trafficking than in Florence.’ John was one of the Avignon popes.

John XXII was also heavily involved in another conflict which rocked the medieval church: evangelical poverty.

Francis of Assisi had founded an order of friars who were devoted to a life of simplicity, austerity and poverty. The original rule was strict and uncompromising. However, with time and as the order spread and it became involved in missionary work, preaching and education, the rule was relaxed, and Franciscans were allowed to own property and the rule was given a more worldly interpretation.

This provoked a backlash and a group, known originally as the Fraticelli and then as the Spiritualists, maintained a firm hold on the original rule and ignored repeated papal appeals to toe the official line. The more radical groups were declared heretics and condemned. Eco’s novel resonates with many references to this debate, and he informs us that the Fraticelli found inspiration in the prophecies of Joachim of Fiore. In a discussion with William, Jorge pours scorn on the founder of the Franciscans and calls him ‘the clown of God.’

A young Franciscan, Gerard of Borgo San Donino, was a confirmed Joachite. He edited some fragments from Joachim’s writings and published an ‘Introduction to the Eternal Gospel,’ where he claimed that the Antichrist, the incarnation of all evil, was already active in the second status (Joachim had divided sacred history into three status: the old dispensation - the Old Testament period; the second status of Jesus Christ, and a final pouring of the Spirit in the last days). Gerard was treading upon dangerous ground when he claimed the Antichrist was now at work to undermine and destroy the present Church in 1260 and that the third status would basically be a Franciscan operation when the sacred scripture would be the Joachite writings known as the Eternal Gospel. We can understand how these ideas were disturbing and provocative.

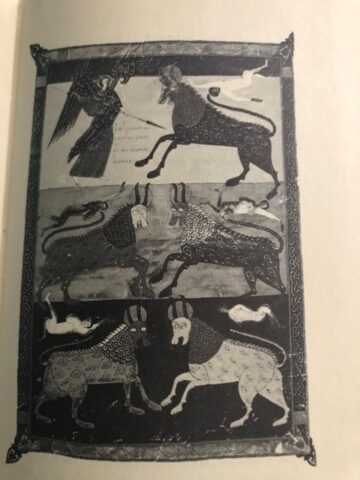

The best evidence for the expectation of the end of days comes from Spain. A classic case concerns Beatus de Liébana who wrote an extensive commentary on Revelation, and which is mentioned in our novel. Beatus’ commentary on Revelation 7:4 states that there are only fourteen years left for the coming of Antichrist. Beatus’ commentary is famous in the history of Western apocalypticism for the splendid illuminations that grace the 26 surviving copies of his book. These include not only portrayals of the monstrous images of Antichrist such as the Beast of Revelation 13, ‘I saw a beast rising out of the sea, with ten horns and seven heads, with ten diadems on its horns and a blasphemous name upon its heads’, but also pictures of the human Antichrist. Eco published a slim volume called ‘Reflections on The Name of the Rose’ which includes some of the Beatus illustrations.

But life in the monastery is not all spiritual endeavour and mortification of the flesh. We learn that Adelmo, who is handsome and effeminate, has had a homosexual relationship with Berengar. Though he confesses to Jorge, he is driven by guilt to suicide. When Adso is leafing through the Beatus manuscript his eyes are drawn to the ‘mulier amicta sole’ - the woman clothed with the sun. This woman struck Adso as being extremely beautiful, but he receives a shock when he set eyes on the whore of Babylon. Both figures are derived from Revelation, and they defined the contrasting images of femininity which haunted the mind of medieval monks. Gazing at these suggestive pictures of womanhood is a prelude to Adso’s own sexual awakening. While in the monastery kitchen, he becomes aware of someone else’s presence: an adolescent woman who seduces him. Adso lacks any knowledge of secular love poetry, so he gushes with the incandescent love phrases from the Song of Songs, still the most erotic poem ever written and part of the Hebrew Bible. Adso, though a monk, seems unaware that this love poem had already been interpreted allegorically by Bernard of Clairvaux in a series of sermons. Bernard’s version became the standard reading of this collection of love poems and even as late as the seventeenth century, it was still the accepted reading in Saint John of the Cross. But Adso is swept by sexual desire and cries out: ‘Suddenly the girl appeared to me as the black but comely virgin of whom the Song of Songs speaks’. ‘Her eyes were clear as the pools of Heshbon…’. Adso confesses his sin to William who is indulgent and forgiving.

In many conversations with the dour Jorge, we learn he disapproves of laughter. He claims laughter is proper to monkeys, not human beings. Moreover, there is no record that Jesus ever laughed. William counters that with the remark that monkeys grimace but don’t laugh. Laughter is proper to human beings, as a sign of our rationality. And some of Jesus’s sayings convey a sense of humour - witness his comment about the eye of a needle and the camel. But laughter is no laughing matter in the novel.

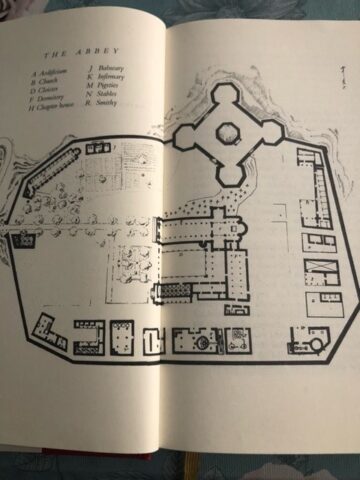

Jorge’s mission is to prevent Aristotle’s treatise on laughter from becoming well known - it would invest laughter and frivolity with an aura of respectability and shatter the sober and serious atmosphere of the monastery. In his endeavour to frustrate William and Adso’s attempt to rescue the Aristotelian masterpiece, he starts eating the pages of the book in a parody of the eucharist, stuffing them into his toothless mouth and, in the commotion in the library, Adso upsets a lamp which sets fire to the library which then spreads to the rest of the Aedificium. ‘Now I saw tongues of fire rise from the scriptures,’ cries Adso, in a vision which parodies the event of Pentecost. There is a sense of justice prevailing as, all along, it was Jorge who was behind all the murders. Now he is consumed by the library fire and the greatest library in Christendom is doomed. William identifies Jorge with the real Antichrist.

The novel is divided into seven days and structured around the liturgical hours: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vesper and Compline. As we read, we seem to be following the monks in their daily round of prayer, meditation, manual labour, clerical tasks, reading and creating works of art, the illuminated manuscripts which are the glory of the medieval scriptorium.

Ideally, The Name of the Rose requires extensive annotation if the reader is to follow the meandering narrative and absorb the different layers of meaning Eco has injected into the long conversations and disquisitions.

My attempt, though limited and brief, should at least alert the reader to the effort needed to appreciate the full range of meanings the novel encapsulates. The title alone is enigmatic and not easy to comprehend. Adso’s account, which is what we read, ends with a confession by the writer that he no longer knows what it is all about. This discouraging disavowal is further reinforced by the concluding Latin hexameter which Eco does not translate for us: stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus. In English: the rose of old remains only in its name; we possess naked names.

William is a disciple of the iconoclastic medieval philosopher William of Ockham. Ockham rejected the universals which were part of the scholastic synthesis forged by Thomas Aquinas. Ockham believed only individual entities existed, universals were mere words with no real existence outside the mind. Eco’s Latin line about the rose is pointing out that the whole world created in the novel is just a gathering of mere words and that is all we can aspire to. Ockham’s famous razor cuts out the unnecessary and superfluous, whittles the novel down to a mere flower.