Gibraltar’s Spiritual Centre: Rethinking the Origins of the Cathedral of St Mary the Crowned

This is the final instalment in a three part series written by Carl Viagas. The series was published weekly on Mondays.

The recent investigation of the Cathedral roof void—brought to public attention through the important article by Dr Ryan Aquez—has opened a new chapter in Gibraltar’s understanding of its own architectural and religious history. The careful removal of the 1960s asbestos roof has granted researchers a rare opportunity to examine deep-set medieval masonry, blocked apertures, and long-hidden structural layers above the altar.

These discoveries have not only enriched the historical narrative of the Cathedral but have also provided new evidence that invites a reconsideration of Gibraltar’s earliest sacred landscape. The work carried out by the Cathedral team, the contractors, and the small group of historians and specialists who documented this previously inaccessible space deserves recognition for its meticulous execution and the extraordinary contribution it makes to Gibraltar’s heritage record.

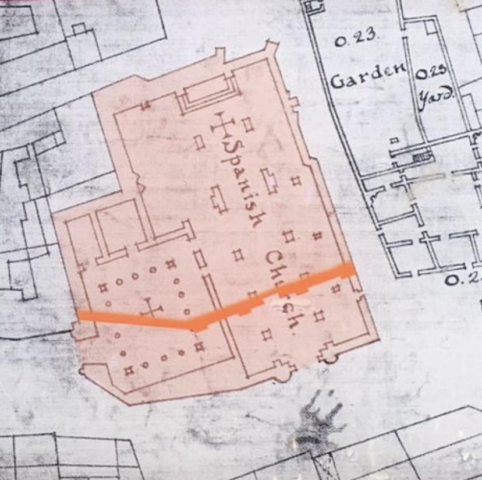

One of the earliest plans showing the original structure of the Cathedral. Its main west wall no longer

present, marked in orange. Note the main building with central nave leading to the altar, and two lateral naves. The courtyard appears attached to the north of the main building and no Qibla wall facing Mecca is present.

This article builds on that work to explore a broader question: does the Cathedral sit on a site far older than previously believed? The emerging architectural evidence strongly suggests that Gibraltar’s principal sacred building may predate the Marinid mosque traditionally thought to be its origin. Indeed, when considered alongside settlement patterns, structural analysis, and historical texts, the case for a pre-Islamic Christian foundation becomes increasingly compelling.

A Site Older Than the Marinid Mosque

The familiar narrative asserts that the Cathedral stands on the site of the mosque constructed by the Marinids after their reconquest of Gibraltar in 1333. Yet, the existing building fabric challenges this view. A mosque of such date and importance would have had to conform to established Islamic architectural norms, including an orientation towards Mecca and the presence of a mihrab niche marking the qibla wall. None of these elements exist in the Cathedral’s surviving structure. The building’s longitudinal axis bears no relationship to the southeast-facing direction of Mecca, and no archaeological investigations—past or recent—have identified any trace of a mihrab, minaret base, or sahn courtyard. These absences are not minor or ambiguous: they strike at the architectural foundations of what a Marinid mosque must have been.

Instead, the Cathedral’s spatial organisation aligns more closely with medieval Christian ecclesiastical

planning. The sanctuary area, the distribution of structural loads, and the massing of walls all reflect the principles of European church construction rather than Islamic religious architecture. This suggests

that the present-day Cathedral was not built simply by converting an existing mosque, but rather that earlier Christian structures may lie beneath its later layers.

The style of the arch is comparable to Romanesque architecture than to the Gothic pointed arch. Its condition (significant weathering) even though protected may reveal its true age.

Findings from the Roof Void

The newly revealed roof void above the altar adds considerable weight to this interpretation. The exposed masonry shows phases of construction that are neither uniform nor consistent with a single medieval Islamic building. Different layers of stonework, plaster, and blocked openings indicate that the structure underwent multiple phases of Christian use long before the 16th-century Gothic rebuilding under the Catholic Monarchs. Some of the oldest sections appear thicker, deeper set, and more robust than Marinid-era construction typically found elsewhere on the Rock.

In particular, the void has revealed:

i)

deep medieval masonry that predates 16th-century works;

ii)

structural alignments incompatible with mosque design;

iii)

blocked medieval apertures that do not relate to Islamic layouts;

iv)

multi-layered lime mortar finishes revealing periods of reconfiguration.

These findings are consistent with a site that has served as Gibraltar’s spiritual nucleus across several centuries of religious change, rather than a location that began its life solely as an Islamic place of worship.

The fluted columns are not consistent with typical Islamic architectural design. This essential structural component may provide another hidden clue as to this building’s true origins.

Settlement Patterns and Early Christian Presence

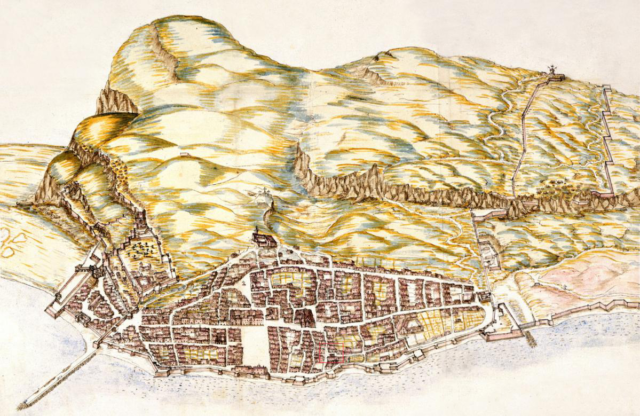

The argument for a pre-Islamic Christian foundation is strengthened when placed in the context of medieval settlement patterns. As discussed in the earlier Chronicle article on Gibraltar’s founding, the earliest urban organisation appears not in the Villa Vieja district—long assumed to be the core of the medieval town—but around the Cathedral precinct itself. This area occupies a strategically advantageous position: elevated, defensible, near fresh water sources, and overlooking the harbour. It is precisely where a late-antique or early-medieval community would logically establish its religious centre.

Above: Luis Bravo Plan 1627. Shows the location of the Cathedral at the heart of the

Town.

Such continuity of sacred space is common across the Mediterranean world. Many Christian churches were built atop earlier Roman, Visigothic, or Byzantine places of worship, and later Islamic rulers often adapted existing Christian structures for use as mosques. The possibility that Gibraltar followed this same pattern is entirely consistent with regional architectural traditions.

Why the Cathedral Was Unlikely to Have Been a Mosque

Beyond the issues of alignment and absence of Islamic elements, several architectural features reinforce the improbability of a Marinid mosque occupying this site:

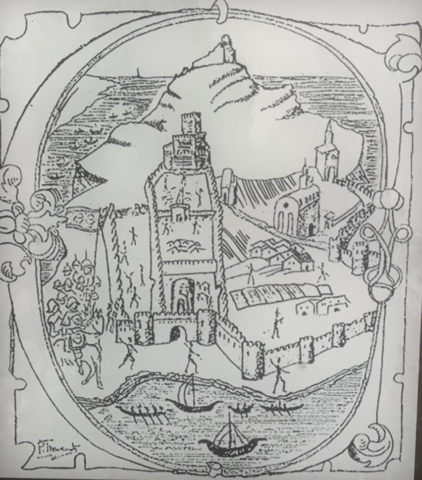

Above: image depicting the capture of Gibraltar by the Duke of Medina Sedonia.

Note that the depiction of the Cathedral does not resemble a mosque with its minarets but is more akin to a basilica. Artistic license? Perhaps.

i)

The sahn (courtyard) exists as an appendage to the main building, not as the essence and focus of a Marinid mosque.

ii)

No structural evidence of a minaret or stair turret has ever been found.

iii)

The thickness and composition of walls are more consistent with Christian ecclesiastical construction and not the Gothic 16th century style.

iv)

The Gothic architectural style, which is often quoted, is not present. No flying buttresses, gothic arches or clerestory windows all which are key and distinguishing features which define such architecture.

v)

The deep-set sanctuary area and raised chancel belong to medieval Christian design principles.

These factors, taken together, create a strong architectural argument against the mosque hypothesis.

Gibraltar’s Spiritual Anchor

Across centuries of political change—from Islamic rule to Castilian governance, from Habsburg sovereignty to British administration—the Cathedral has remained the fixed spiritual centre of Gibraltar. Its endurance reflects not only religious continuity, but also the physical durability of the underlying structure. As the newly exposed roof void is examined in greater detail, it becomes increasingly plausible that the Cathedral preserves the earliest sacred architecture on the Rock.

Above: Artist impression of Gibraltar after the Great Siege where the ruins of main street are captured. Notice the cathedral, even though damaged is still standing. Its architecture seems to reflect that of a

Visigoth church.

As seen in this image below:

Typical Visigoth church (San Pedro de la Nave 7th C) showing an architectural style very different to the later Gothic architecture of the Middle ages. Note heavy construction, few window openings, no flying buttresses and relatively low tower.

Conclusion

The recent roof void investigation has brought Gibraltar closer than ever to understanding the true antiquity of its principal sacred building. The absence of Islamic structural signatures, combined with emerging evidence of earlier Christian phases and the strategic settlement patterns of medieval Gibraltar, strongly suggests that the Cathedral of St Mary the Crowned stands on a site whose origins reach back before the Marinid period—possibly even before the Almohad fortifications of 1160.

The work carried out in the Cathedral’s hidden spaces deserves the highest praise. It has revealed not only forgotten architecture, but a forgotten history—one that challenges established assumptions and invites Gibraltar to re-examine the roots of its spiritual identity. As further investigations continue, the Cathedral may yet reveal more of its ancient secrets, helping to shape a richer and more nuanced understanding of Gibraltar’s early past.