Newly exposed base of Spanish wall reveals the extents of Gibraltar’s ‘second line of defence’

This is the first in a three part series written by Carl Viagas. The series will be published weekly on Mondays.

Clearing out work in the Northern Defences continue to uncover long-buried sections of military defensive lines. During the last two months the lower section of a Spanish wall dating back to 1627, sheds new light on Gibraltar’s pre-British fortifications and confirming details recorded in early eighteenth-century British reports.

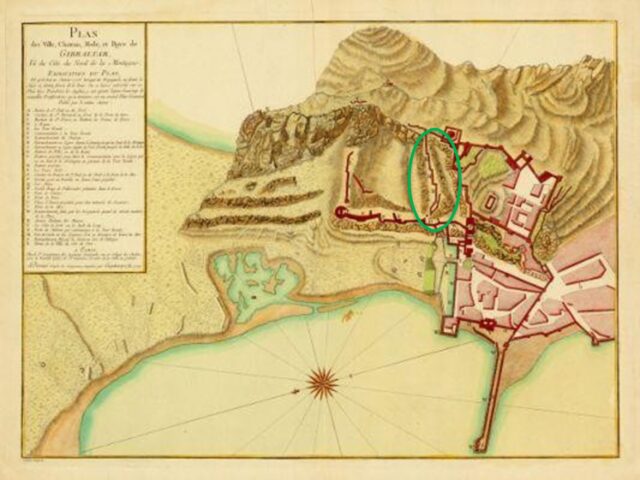

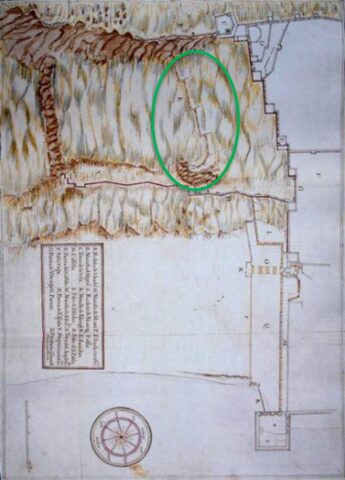

Known historically as El Muro de San Joseph, the upper section of the wall was uncovered in 2019 as part of the clearing out works to the northern defences. This wall, later referred to as Hanover Line, formed part of a complex series of defensive lines constructed during the Spanish period. When British forces seized Gibraltar in 1704, they described this wall as the “second line of defence”, a designation that hints at its strategic importance.

Today, more than 300 years later, its lower section is once again visible. For project manager Carl Viagas, the uncovering adds a crucial new layer to the evolving story of Gibraltar’s military past.

“Every excavation here is like peeling back history,” he said, standing beside the newly

revealed stonework. “This wall is a reminder that our fortifications were not created all at once but developed in successive waves, each responding to the warfare of its age.”

The wall was first revealed after vegetation clearance and careful excavation. Its base courses, still remarkably intact, show the deliberate Spanish engineering of the early seventeenth century. Thick rubble masonry bound with mortar created a defensive barrier capable of withstanding small arms and crossbow fire — the weapons of its time.

Unlike the later British entrenchments, which adapted to the power of cannon, El Muro de San Joseph reflects an earlier stage of military architecture, when Gibraltar’s defenders sought to slow and channel enemy assaults up the Rock’s northern approach.

The excavation also exposed stone and clay tiles steps adjacent to the wall, suggesting access routes for soldiers manning the line. Their orientation makes clear that this was no agricultural terrace or retaining wall but a deliberate military feature, built as part of a wider system of layered defences.

The name Muro de San Joseph appears in Spanish records and was later repeated by British officers who surveyed their new possession in 1704. For them, the wall marked an organised, recognised line of resistance — not a minor outwork but a structured part of the Rock’s defensive grid.

“The fact that the British, fresh from capturing Gibraltar, referred to this as the ‘second line of defence’ is significant,” explained Mr Viagas. “It means that what we are looking at today was not just a wall but an entire defensive position, part of a system that the Spanish themselves considered vital. A defensive line that the combined Anglo Dutch force avoided during the capture of Gibraltar”.

The discovery ties neatly into the wider theme that has emerged from recent work on the Northern Defences: Gibraltar’s fortifications are best understood not as a single construction but as a “military manuscript” — where successive generations building over, adapting, or burying the work of their predecessors.

In this case, the Muro de San Joseph predates the sweeping British trench systems that dominate the site today. When artillery became the defining force of warfare, older vertical stone walls like this one became obsolete. The British buried and built over them, creating new angled works and deep trenches to deflect cannon fire.

Ironically, this very act of burial preserved the Spanish wall. Hidden beneath rubble for centuries, it has now re-emerged as testimony to an earlier era of siege warfare.

To appreciate the wall’s significance, it helps to recall the political and military context of the time. One where Spain, having sustained a pirate attack, embarked on strengthening its defences against renewed threats.

The Muro de San Joseph was part of this wider programme, a conscious effort to reinforce the Rock’s vulnerable northern approach — the only landward access for enemy armies. At a time when siege craft relied on infantry assaults, scaling ladders, and field artillery, strong stone walls backed by infantry firepower could mean the difference between holding or losing the fortress.

By 1704, when Anglo-Dutch forces captured Gibraltar during the War of the Spanish Succession, such walls were still noted in military reports. But within a generation, military technology had moved on. Cannon and mortars demanded new defences, and straight masonry walls gave way to entrenchments and subterranean galleries.

For Mr Viagas and his team, the rediscovery of the wall offers not just a physical structure but a fresh way of reading Gibraltar’s landscape. “When you clear the undergrowth and start to see these features align with others, it’s like the map redraws itself before your eyes,” he said. “The wall connects with routes, steps, and other elements that make sense once you understand them as part of a layered system of defence.”

Already, the find is prompting new questions. How exactly did the Spanish intend this second line to function alongside the earlier Moorish Castle and the Landport area? Was it primarily a fallback line in case of a breach, or did it serve as a rallying point for counter- attacks? Further excavation and archival research may yet supply answers.

This discovery also highlights Gibraltar’s enduring challenge of heritage management. The Northern Defences, overgrown and neglected for decades, are only now revealing their secrets thanks to systematic clearance and excavation.

Each new find — whether the Round Tower, the Puerta de Granada’s true function, or now the Muro de San Joseph — demonstrates the value of sustained investment in heritage.

Mr Viagas credits the Gibraltar Government, particularly Dr Joseph Garcia and Dr John Cortes, with supporting this renewed effort:

“Without their commitment, much of this history would still be hidden under rubble and vegetation. What we are doing now is not just excavation, but restoration of

memory.”

The exposure of the Muro de San Joseph will now form part of ongoing interpretation of the Northern Defences. Its story complements recent discoveries that challenge long-held assumptions about Gibraltar’s medieval and early modern history.

As the wall stands in the sunlight once again, it serves as both a physical reminder of the Rock’s contested past and a metaphor for history itself: sometimes buried, sometimes forgotten, but never gone.

“Every time we uncover a wall like this,” Mr Viagas reflected, “we are not just seeing stones.

We are seeing choices made by soldiers, engineers, and rulers centuries ago. And those choices shaped Gibraltar’s survival.”