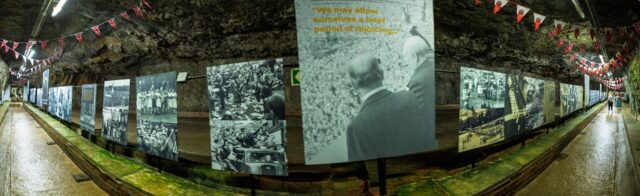

Secrets of the World War II tunnels explored on Walks Through History

Photos by Johnny Bugeja

By Neve Clinton

The Gibraltar National Museum’s ‘Walks Through History’ took children on a tour to uncover ‘Secrets of the WWII Tunnels’, as part of the GSLA summer sports and leisure programme.

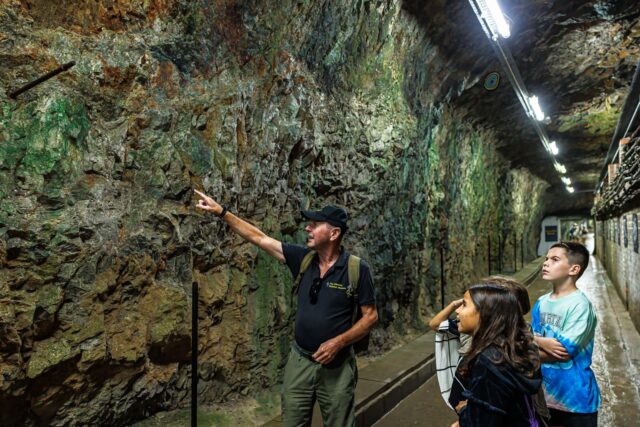

The walk was led by Senior Guide Phil Smith, with the nine to 12 year-olds enjoying a tour of the newly refurbished WWII Tunnels attraction, learning all about how soldiers constructed the tunnels and lived inside the Rock during the war.

“When they started making the city inside the rock, that city was going to be home to 17,000 soldiers, who would live inside the tunnel, they would have everything they needed, places to sleep, a canteen and a kitchen, places where they could wash and shower, they got water and fuel storage tanks, they got hospitals, they even got their own bakery”, Mr Smith said.

He explained that the tunnels were constructed using a combination of drilling and explosives, with engineers drilling holes in the rock and placing explosives in a “necklace” formation of rings.

This had a central charge making the initial hole, and then surrounding rings with charges directing the collapse outwards, in a controlled, circular way rather than one large blast.

Engineers set off these charges in sequence using timed fuses, allowing workers to take cover.

According to Mr Smith, this was the most efficient method to clear the way, after which old-fashioned drills were used to tidy the tunnel shape.

The children were then shown the Spitfire on display, which Mr Smith explained was the fastest plane in the RAF during WWII, designed by Reginald Mitchell.

They would be sent to Gibraltar part-assembled in crates, and re-assembled on the airfield, taking a team of six to eight men a week to complete.

Mr Smith added that this particular Spitfire, with the name ‘Gibraltar’ printed on it, was an exact replica of the original aircraft sponsored by the people of Gibraltar and named in their honour, which unfortunately crashed during an accident in Scotland, with lots of the pieces left there and only found a few years ago.

10 year-old Stella Celeste Fernandez said the Spitfire was the highlight of the tour for her, and she also appreciated the newly added exhibition.

Mr Smith then showed them what used to be the kitchen which he said was, very strangely for 1940, powered by electricity, while everyone else at the time was using coal or gas.

“Here, they pioneered the use of electricity for large-scale cooking,” he said.

“The advantage [of electricity] in the tunnels is that you've got much less risk of there being a fire. You haven't got any smoke or fumes, so it keeps the air clean in the tunnels”.

He added that the majority of food the soldiers got were army rations, in boxes and tins, but they tried to supplement it with fresh fruit and vegetables collected from markets in Tangier during ship patrols of the strait, attempting to supplement their diet with foods rich in vitamin D to compensate for the lack of sunlight in the tunnels, which could lead to illness.

“They also had powdered egg and you mixed powdered egg with water and it became like scrambled egg. It got the same texture as it, but it came in this cardboard tube and I've been told that the cardboard tube was tastier than the powdered scrambled egg”, he added.

Further into the tunnels, Mr Smith showed the children an example of the Nissen huts soldiers used to sleep in to keep dry inside the porous rock, and told them that the standard design included windows but “when the soldiers were looking through the windows, they could just see the rock, and it upset them psychologically”.

“They didn't know what to do. So, they came up with a clever solution then that instead of using clear glass, they used frosted glass, so you can't see directly through it”, which made them feel better.

As they approached the sign stating “Liddell’s Union”, Mr Smith said “to keep the existence of this city inside the Rock a secret, they were never called tunnels. They'd always got a different name, like down by the hospital was a tunnel that they called Harley Street”.

“This one is called Liddell's Union. General Liddell was the governor at one time, and this union links up the northern part of the rock to the southern part of the rock.”

As they walked through the standard “communication” tunnel, a corridor made for people to walk up and down, they approached a fissure cutting across the rock, opening up to a chamber, which Mr Smith said the engineers had stumbled upon while drilling to make the tunnel.

“Just up here they got a very big surprise… So they're drilling for weeks and weeks into solid rock and all of a sudden they fall forward into this area. Saved them a couple of days’ work.”

He highlighted the stalactites here which had formed curtain stones, appearing to flow down with folds that look like curtains hanging from the sides of the narrow fissure.

“Today, this is very dry. If you come here in November, there's so much rain coming down here it's like a waterfall, and if you're doing the tour, what you have to do, you get to that point there and you run as fast as you can, and once you get into the next bit it's dry.”

Further along the corridor Mr Smith brought his torch out and pointed out the names that had been etched into the walls.

“A lot of the soldiers who were living inside the tunnels, just for the fun of it, would write graffiti, would leave their names in the walls”.

“If you have a look just here F. Perks, S. Murphy, 1942. And that's T. Maguire, 1942. Watts, Perks, Murphy. And this one here you can't see it very clearly but this actually says 103rd Auxiliary Works Company, Royal Engineers. The Auxiliary Works Companies were the ones who fitted out the accommodation blocks.”

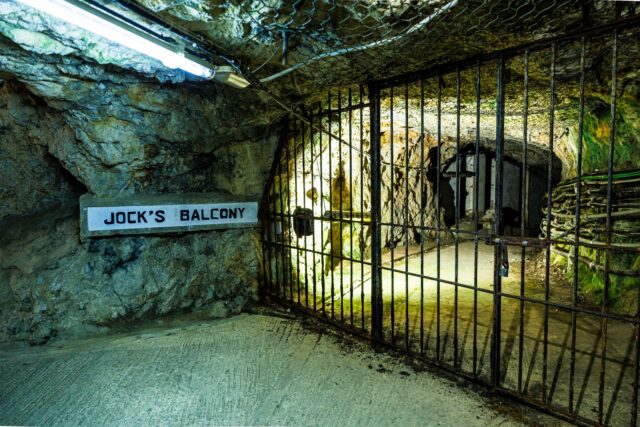

Arriving at the balcony on the Northern end of the tunnel, Mr Smith said: “This area here is called Jock's Balcony, Jock is a nickname for Scotsman, and there was a Scottish battalion here called the Black Watch, and this was the place they built”.

“Originally it was an observation post to watch for any troop movements, but later on it became the place where you finished work and you went out to get fresh air and have your cigarette.”

Looking out at the view of the runway from the balcony Mr Smith added that half of the length of the runway was reclaimed from the sea using the rubble from digging out the tunnels.

Concluding the tour Mr Smith told the young historians: “The length of all of the tunnels was over 50 kilometres, the bit we've seen today is just 500 metres. So today we've seen 1%, just 1% of Gibraltar's tunnel system. The other 99% is still there for us to explore”.

Eight year-old Tamar Ben Mordechai, told the Chronicle that she learnt “the WWII Tunnels had loads of people living there for loads of time in secret, a city under the rocks”, highlighting that her favourite part was seeing how they lived, displayed through mannequins.

She also added that she liked that there were “things you can interact with” in the recently refurbished exhibition area.

Stella Fernandez added that the most interesting fact she had learned was that “the tunnels were used in the WWII and then a lot of soldiers from different countries came to learn how to tunnel fight in Gibraltar, and we were called the like ‘masters of tunnels’”, with Mr Smith explaining that during the Afghanistan conflict, Gibraltar’s tunnels became relevant again.

Initially deemed obsolete after WWII, tunnel warfare resurfaced in Afghanistan, leading the Gibraltar Regiment to become the British Army’s experts in the field, training extensively and hosting NATO forces from various countries for practice.