The ‘Little Blitz’

In this two-part series Joe Gingell looks back at World War II and has shared his and fellow Gibraltarians recollections when evacuated in London. This is the first part of the series. Part two will be published in tomorrow’s edition.

By the end of 1943, Germany was fighting alone after Italy had surrendered in September 1943. The Russians were on the offensive and the Japanese expansion had been halted. The military authorities considered that Gibraltar was no longer vulnerable to enemy attacks and therefore saw no reasons not to allow the repatriation of the evacuees. The Governor of Gibraltar then also visited London to discuss with the British Government the arrangements to be followed for the repatriation of the evacuees. By then some of the men who had stayed in Gibraltar working on essential services were given special leave to visit their families in London. The heavy aerial bombardment had receded considerably since the end of the Blitz in May 1941. Having endured three years of bombing, with relatively few fatal casualties there seemed to be the general belief amongst evacuees that they were blessed. This seemed to have also led to the notion that the Londoners, during an air raid, wanted to be near the Gibraltar evacuees! There was an air optimism among the evacuees of a victorious ending to the war. Also, that they would soon be repatriated and reunited with their families. What was, obviously, not known then was that the worst of the bombing of London was still to come - with heavy casualties and that many evacuees were going to have to wait for a very long time before being repatriated!

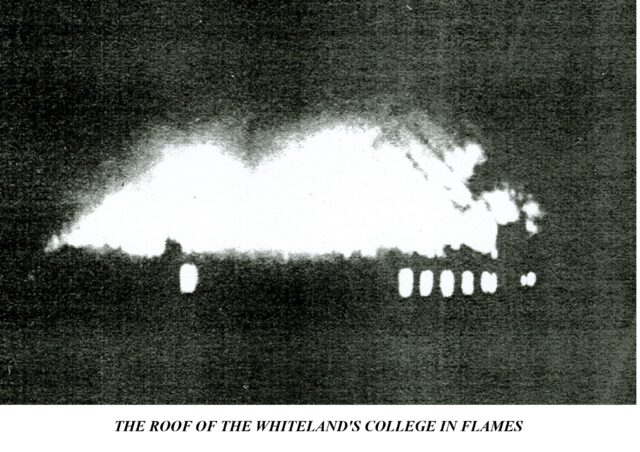

As from January 1944, in retaliation for the intense bombing of the German cities by the Allies, the Luftwaffe attacked London with so much strength that this spate of bombing became known as the “little blitz.” During that spate of bombing, in Putney, where there were 1,000 evacuees, there was air raid that lasted for one and quarter hours. Amongst the bombs dropped were 100 incendiary containers, each holding 620 bombs- a total of 62,000 bombs! The night of 18 February, the fire watchers at the Whiteland’s College had been alerted that the Germans were going to drop lots of incendiary bombs all over London to prepare the way for a spate of heavy bombing. In the early hours of the 19th February 1944, the fire watchers at the Whiteland’s College began to observe small parachutes that were releasing containers which on reaching a certain height started to explode igniting buildings and their surroundings. By then all the firewatchers were ready with their stirrup pumps and buckets full of water to put out the fires. The evacuees who were already in the shelter on hearing about the incendiary bombs came out of the shelter to collect whatever they could from the burning building. Others were watching their rooms already in flames. Most of the women and children were grouped in the playing fields surrounding the building whilst the grown-ups tried to salvage personal effects. The fire brigade had been very busy that night with fires all over London. By the time they arrived at Whiteland’s, the roof of the building was completely ablaze. All the evacuees who lived on the top floor had lost all their belongings. That morning had been snowing slightly and was freezing. I was then nearly 6 and distinctively remember that when we started to leave the building, the corridor was very badly lit and there was a lot of smoke coming from the fire caused by the incendiary bombs. As our room was on the first floor, we were not very far from the fire escape doors and so managed to get out of the building very quickly. My mother covered me with blankets and placed me near a tree well distant from the building. From this spot, I remember seeing the roof burning and flames protruding from the windows on the top floor.

In the meantime, my mother and my two brothers who were older than me, went to salvage some of our personal belongings. My mother used to say that the night that the Whiteland’s was bombed she had noticed seeing fires all over London. After a long wait sitting on the humid and cold grass, an army lorry arrived and began to take away the evacuees to be accommodated in other places. During my research I found out that my family was taken to a monastery at Lancaster Gate where we were given some hot drinks and then slept for the rest of the night. A few evacuees were offered to stay in some of the houses in the periphery of the Whiteland’s College. Other evacuees, who were at the Whiteland’s College and with whom I spoke with during my research, gave the following personal experience of the night of the bombing of the Whiteland’s College.

Hector Alecio although very young, he explained that on the night of the bombing of Whiteland’s, some evacuees got to know that the Germans were dropping lots of incendiary bombs to prepare the way for a spate of heavy bombing. That night Hector recalls that there were big fires all over London.

YolandaTribello (nee Bacarese) “My family were all in the shelter except my uncle Angel D’Alorto who was on fire watching duties. He had just gone to tell my aunts Aurelia D’Alorto and Francisca Pratts to rush to the shelter but before reaching the shelter we got to know that an incendiary bomb had hit the room where we lived. We later found that everything we had had been burnt, including my toys.”

Arturo Harper

“That night many of the residents had gone early to the shelter. My father was like many other men on fire watching duties. He noticed from experience that there was going to be an air raid that night. He went to tell those who were still in their rooms to move quickly to the shelter. When they were about to go down to the shelter, the word got round very quickly that the building had been hit by a bomb. Those who were already in the shelter also got to know of the bombing and wanted to get out of the shelter. Inevitably there were some clashes along the staircase between those who wanted to get in and those who wanted to get out of the shelter. There was for a while a great confusion which lasted until eventually everybody began to realise that they had to leave the building. By that time there was a lot of smoke in the corridors and many panicked and some even fainted.”

Salvador Lopez Explained how with the aid of stirrup pump and a bucket of water he helped to put out a fire caused by an incendiary bomb that had come through a window and landed on the corridor of the top floor which was full of black smoke and a horrific smell of acid. By covering his mouth and nose with a wet handkerchief tied to the back of his neck, he aimed the hose in the direction of the fire and started pumping. Despite several attempts, the fire was just as fierce. He managed to find a bucket which he filled with water from a bathroom nearby and poured it on the fire. By then almost everybody had left the building. One of the bombs had gone through the rafters setting the top floor on fire. When coming down the stairs, he heard lots of noises and got to know that his family were looking for me. Salvador also explained that when he left the building with his brothers he sat with the rest of the residents on the grass. At that moment and as a 14-year-old boy he said that he remembered feeling very proud of having helped to put out the fire. He, said, “I remember that they were all clutched to whatever possession they had managed to collect and watched how the rooms were burning little by little. Most of the women and children were grouped in the playing fields surrounding the building whilst the grown-ups salvaged personal effects and helped as best as they could. The fire brigade had been very busy that night and by the time they arrived at Whiteland’s the roof of the building was completely ablaze. All the evacuees who lived on the top floor had lost all their possessions.”

Luis Saltariche who was then about 4 or 5 years old remembered how he was grabbed and then carried on the shoulder of a firewatcher who took him to the playground.

Zoriada Santos (nee Hermida) who was then about 11 recalled that they lived on the top floor. She explained that when they came out of the shelter all they possessed was what they were wearing. “My mother had a handbag where we kept our passports and some money – the rest of our belongings were lost in the fire,”

Aurelio Bellido

Aurelio was on leave after serving in the dreaded Artic Convoys on HMS Fulknore. He had been celebrating his reunion with his family at Whiteland’s a few hours before the bombing. He probably had had one too many and went straight to bed. Alfredo Balban who knew that Aurelio was still sleeping went into the room and carried Aurelio on his shoulder until he was safely out of the building.

Claudio Olivero

On the night of the bombing, he was on shift work and did not get to know about the bombing until he arrived at Whitelands from work at about six in the morning. He said that when he arrived there was a lot of smoke coming from the building and although he had told the fire brigade and the police that his family and him lived at Whiteland’s they would not let hm pass.

John Reading

He was about 4 years old and remembered that when they went back the next day to pick up their belongings, he was very saddened to see the state of his toys. “I had a toy horse, which was made of some sort of cardboard material. When we entered our room, the toy horse was floating and disintegrated in the water that been poured by the fire fighters to extinguish the fire”

Adolfo Bosio

“We returned to Whiteland’s the day after the bombing to look for our things and found that everything was completely burnt. On top of a burnt chest of drawers there were a few coins stuck together.” As a result of the intense heat the coins had almost melted, as in the photo showing the melted coins consisted of a 2 shillings coin, a 6 pennies silver coin and two 1 penny coins. Adolfo’s family still keep the melted coins as a memento of that terrible night at Whiteland’s College. From the information I gathered during my research, the Whiteland’s centre, was perhaps the only centre where the evacuees had attempted to put out the fire caused by incendiary bombs but naturally without succeeding and luckily without any casualties.

On the same night of the Whiteland’s’ bombing, there were other buildings similarly bombed, unfortunately, with casualties.

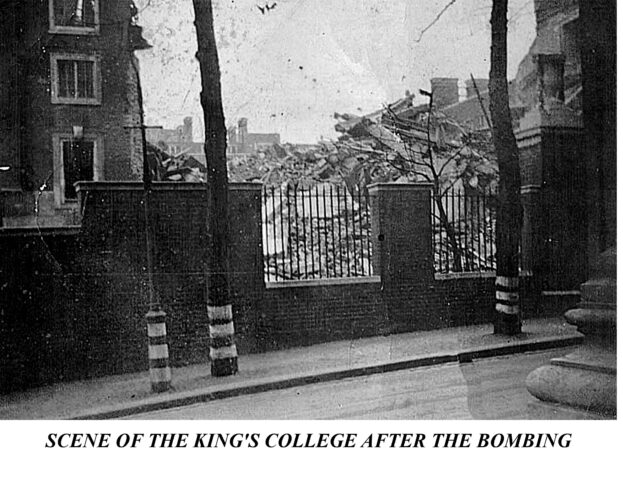

Between the nights of the 18th and 20th of February 1944, in addition to the bombing of Whiteland’s College, three other evacuation centres had also been hit. A high explosive bomb hit the King’s College at Campden Hill Road, in Kensington with residents having to be evacuated to neighbouring hostels. Although there were no casualties from the actual bombing it was reported that a Mr Joseph De Soiza had suffered a heart attack during the incident and died the next day at the hospital.

Incendiary bombs also hit the Royal Stuart Hotel at Crowmwell Road, burning the roof of the hotel. The evacuees were transferred to the Moscow Mansion Buildings. Incendiary bombs also hit the Constance Hotel at 23 Lancaster Gate. Residents were moved to the evacuation centre at 100 Lancaster Gate. Fortunately, there were no casualties in any of these bombing incidents.

Also in Putney, a high explosive bomb hit the area where there was a pub called Telegraph Inn. The pub being very near the Highlands Heath evacuation centre was very often visited by the evacuees. It was also a very convenient meeting place whenever there was a football match in an area near this pub. At the end of the match, many players from the home, visiting teams and spectators gathered at the Telegraph Inn pub to chat about the football match and have a few drinks. The explosion occurred at a time when there were many people in the bar. A Gibraltarian evacuee known as alias “Patente” used to work at the Telegraph Inn pub cleaning the place, collecting and washing the glasses etc. When the bomb exploded, he was outside the building collecting the glasses from the tables. He was thrown in the air by the blast but, fortunately, escaped without a scratch. Many of those who were actually inside the building were service men who, perhaps, were enjoying a few days of leave. The majority were either killed or seriously injured by the explosion.

The air of optimism that existed then amongst the evacuees was beginning to turn into a nightmare by the ‘Little Blitz.’